This week Canadian tobacco companies raised the price they charge to retailers for cigarettes and other toabcco products. This month the price (per cigarette) went up by 1 to 1.5 cents in in most parts of Canada ($2.50 to $3.60 per carton), as shown in the memo sent by Imperial Tobacco to retailers on December 2nd.

From a public health standpoint, increases in tobacco prices are generally viewed as a good thing. There is a long and robust evidence base that higher cigarette prices lead to lower rates of smoking and lower levels of consumption by those who do smoke.

Price increases by tobacco companies, however, are often implemented in ways which defeat this health objective.

That’s because tobacco companies want to raise prices without causing smokers to quit or reduce the number of cigaretes they buy. For them, prices are an optimizing exercise in increasing revenues on each sale while maintaining a large customer base. To address this challenge, the companies have adopted a number of pricing practices and marketing tactics.

This week’s price increase is a good moment to review 5 pricing tactics they use in Canada.

Pricing tactic # 1: Blunt the impact of price increases by spreading them out

A 60 cent a package increase is much more noticeable to smokers than two 30 cent increases — which is why the companies favour multiple small increases rather than a few large ones.

For example, this week’s wholesale price increase is at least the second set of increases over the year. Manufacturers’ prices were also increased by 1 cent per cigarette ($2 per carton) in May, bringing the annual total increase by manufacturers to at least $4 to $6.00 per carton. There may have been additional increases this year, but the ones cited here were the only ones shared with us by retailers. There is no public registry of tobacco wholesale prices in Canada, as there is in Iceland.

Pricing tactic #2: Disguise price increases behind tax increases

Tobacco companies have a long tradition of timing their own price increases to match any rise in taxes. This week an example of that is shown in the higher price increases that are taking place in British Columbia when compared with the other provinces.

British Columbia is the only province to have timed a tobacco tax increase to the New Year. A $4 per carton increase was included as part of the measures announced by the government in November to discourage youth vaping and tobacco use. (B.C. now has the second highest rate of cigarette tax in Canada.)

Although the B.C. tax increase represents only $0.40 per package of Players cigarettes, for example, the actual increase for smokers will be $0.83. Imperial Tobacco increased the price of that brand by $0.35 per pack across the country and added an additional $0.08 in British Columbia. Upset smokers will blame the government for the increase, not the manufacturers.

Pricing tactic #3: Price segment your brands so that there are cheaper brands available to price-sensitive smokers

For over a decade, tobacco companies have used price-segmentation to divide their brands into higher priced premium brands, mid-range value brands and lower cost budget or super-value brands. Each of these categories had about one-third of the market in 2015, as Japan Tobacco informed Health Canada.

In a market where all cigarette brands are sold at the same price (as was the case in Canada before 2003), a smoker facing a price increase had the options to quit, to cut down or to pay the price increase. With price-segmentation of brands, a fourth option was introduced – the smoker could also choose to switch to a lower priced brand.

In Canada there are no minimum price laws or other legal restrictions on tobacco companies selling brands as lost-leaders or below the cost of production.

Pricing tactice #4: Localize prices to give price-sensitive smokers the option of cheaper retail outlets.

Just over a decade ago, it was illegal for manufacturers to charge different prices to different retailers for the same product. That changed in 2009 when the federal Competition Act was amended, Soon after tobacco companies began charging different prices to different retailers, a practice that was made easier because they replaced traditional wholesale distribution with their own ‘direct distribution’ contracts with retailers.

The conditions imposed on retailers when they purchase cigarettes ensure that the retail price set by the manufacturer is charged by retailers. Retailers who wish to benefit from lower wholesale prices are obliged to restrict their profit (markup) to a lower percentage.

The result is that the same brands of cigarettes are sold at lower prices in some neighbourhoods than in others. An example from our price survey in Montreal in early November 2019 shows how large these differences can be: the price of the same budget cigarette brands (Pall Mall, Philip Morris) was $7.62 per pack in one store and $9.00 and $9.25 per pack only a couple of kilometres away. Even stores in the same chain (eg Couche Tard / Circle K) were charging different prices for the same cigarette brands at different locations.

This pricing practice has allowed the companies to introduce another option for smokers facing a tax or price increase — to switch to purchasing their cigarettes at a cheaper retailer.

Pricing tactic #5: Discourage tax increases.

Most of the price paid by smokers for a package of cigarettes results from the federal and provincial excise taxes that are imposed on them. The World Health Organization recommends that taxes represent at least 70% of the price. Health Canada reports that taxes represent about 64% of the cost of a package of “the most popular price category” of cigarettes: because taxes are mostly at a fixed rate per cigarette this percentage varies by province, brand and retailer.

Tobacco companies want governments to keep taxes lo because a) lower prices will not encourage smokers to quit (and may encourage more young people to start smoking) and b) when taxes are low the companies have more “pricing room” in which they can escalate their profit margins.

Recent reports written on behalf of British American Tobacco and presented to governments in Ontario and Quebec encourage government to abandon excise taxes in favour of alternative tax models or to ensure that any increase is gradual, predictable and small.

And yet their own price increases are equivalent or greater than the tax that they claim will drive smokers to the illegal market. The Quebec government has not increased tobacco taxes since 2014; the Ontario government last raised tobacco taxes in March 2018.

While taxes have stayed steady in the largest provinces, industry prices have climbed significantly. Reports filed with Health Canada show that the average manufacturers’ revenue per cigarette increased by more than 25% between 2017 and the first half of 2019. This is equivalent to $7.40 per carton.

Spotlight on: Cigarette pricing in Montreal

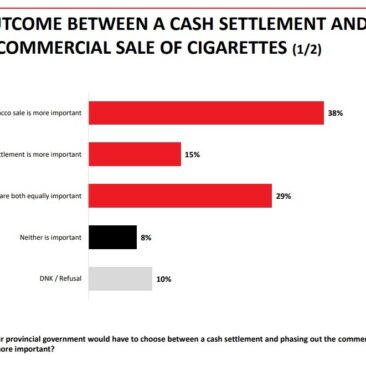

Our survey of posted prices in central Montreal in November illustrates the use of price segmentation and price localization. Montreal smokers who are concerned about price increases are offered the opportunity to switch to lower cost brands and to switch to cheaper retail outlets.

The same survey was conducted in 2018 and 2017. Results from those years shows that the companies have also been successful in grabbing pricing room for themselves and successfully blocking tobacco tax increases.

The companies raised their prices on their cheapest cigarettes by an average of by 33% in only 2 years (from 12 cents to 16 cents per cigarette, or $8 per carton.) By contrast, during the same period, the Quebec government did not increase taxes and the federal government increased them by 1.5 cents per cigarette.

Factsheet:

Results of Montreal price survey: