Most Canadian governments which have banned flavoured e-cigarettes have done so in order to reduce the number of young people who are brought into nicotine use through the use of attractive flavourings. Vaping manufacturers have objected to these measures, and are claiming that flavours “save lives” because they encourage smokers to switch to e-cigarettes.

Missing from this discussion has been a consideration of the additional health risks that flavouring additives introduce to vaping, and the benefits to the health of vapers if the types and quantities of these ingredients were reduced.

Most e-liquids sold in Canada are flavoured. The Vaping Industry Trade Association last year reported to Health Canada that there are “400,000 unique flavouring compounds being utilized in the manufacture of e-substance manufacture in Canada.” That’s about one unique ingredient for every 4 of Canada’s 1.5 million vapers. (They did not provide a list of these compounds, and their estimate is higher than other published information.) [1] Yet current restrictions on e-cigarette ingredients are minimal and often vague.

This post presents background information on (1) current approaches to regulating e-liquid flavours and other ingredients, including Health Canada’s ground-breaking proposals, (2) the flavourants that are currently in use, (3) the risks these chemicals can pose and (4) implications for public health decision-makers.

Part 1: How flavours and ingredients are currently regulated.

Restrictions on what e-vapours smell or taste like

In Canada, three provinces have already implemented prohibitions on selling e-cigarettes that have a flavour or aroma of anything other than tobacco, and two territories have taken steps in this direction. None of these governments have imposed bans on any specific ingredients, but have instead chosen to allow manufacturers to decide what ingredients they can use without causing a “characterizing” flavour.

- Nova Scotia extended the prohibitions in the Tobacco Access Act to include e-cigarettes, effective April 2020 1. Its ban covers tobacco or e-cigarettes which have “a characterizing scent or flavour, other than tobacco, that is noticeable before or during use, or both.”

- Prince Edward Island’s restrictions, which came into force on March 1, 2021. Its Tobacco and Electronic Devices Sales and Access Act Regulations establishes that the flavour bans in its law apply to “an agent added to tobacco or an electronic smoking device to produce an aroma or taste other than the aroma or taste of tobacco, including the aroma or taste of candy, chocolate, fruit, a spice, an herb, an alcoholic beverage, vanilla or menthol.”

- New Brunswick’s Tobacco and Electronic Cigarette Sales Act was modified to ban the sale of any e-liquids that have a “noticeable flavour” other than tobacco. This came into effect on September 1, 2021.

- The Nunavut legislature adopted a new Tobacco and Smoking Act last June which would forbid the sale of e-cgiarettes that “contains an ingredient or combination of ingredients that imparts a distinguishing aroma or flavour, including that of a spice or herb, but not including that of tobacco.” The government has yet to sign this law into effect.

- In late December, the Northwest Territories circulated draft Tobacco and Vapour Products Control Regulations which would ban all vapour products that “impart an aroma or flavour, including that of a spice or herb.. except flavoured vapour products that impart a distinguishing aroma or flavour of tobacco and no other distinguishing aroma or flavour.”

In other parts of the world, seven countries have used the same ‘characteristic flavour’ approach to regulate e-liquid s. That is, they prohibit the sale of vaping products which produce a flavour or aroma that is characteristic of something other than tobacco.

- Finland was the first to introduce this measure (in 2016). The Finnish Tobacco Act (s. 24) prohibits characterizing flavours other than tobacco-flavour in e-cigarettes.

- The two other European countries to have implemented similar restrictions are Hungary (May 2020) and Estonia (2019). Estonia’s law originally banned all flavours but tobacco, but this was amended to allow menthol in 2020, coinciding with the EU-wide removal of menthol from tobacco.

- The four other countries which have adopted flavour restrictions are Denmark (all flavours other than tobacco and menthol, effective April 1, 2022), the Netherlands, (All flavours other than tobacco, effective July 1, 2022), Ukraine (all flavours but tobacco, effective July 2023), and Lithuania’s (ban on flavourings other than tobacco by July 2022).

Four U.S. states (New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Rhode Island) have also implemented bans on e-liquid flavourings other than tobacco-flavour. California’s law is suspended pending the results of a referendum.

Restrictions on flavouring ingredients

Canada’s federal government has proposed a different approach to regulating flavouring ingredients. Instead of only prohibiting flavouring ingredients purely on the characteristics they give to the product, they also propose to limit the ingredients that can be used. Health Canada’s draft regulations, circulated in June 2021, would set a list (‘schedule’) of approved flavouring ingredients (40 flavouring ingredients permitted in tobacco-flavoured e-liquids and 42 different ingredients permitted in mint-menthol flavoured e-liquids). This list is the belt for the suspenders of an additional proposed ban on any “sensory perception other than one that is typical for mint, menthol or a combination of mint and menthol.”

If this regulation is adopted, it will extend the promotional restrictions on flavours that have been in effect since the law came into force in May 2018. Schedule 3 of the federal Tobacco and Vaping Products Act, in force since May 2018, identifies five flavour categories that cannot be promoted in Canada: confectionery, dessert, cannabis, soft drink and energy drink. In Canada it is not illegal to sell an e-liquid that tastes like Cotton Candy, but it is illegal to use a label or promotion for that flavour. This is why such flavours are sold with eupheumistic names “Blue Fluff – Carnival Snack“.

Restrictions for other ingredients in Canada and elsewhere

Governments in several countries have adopted some restrictions on e-cigarette ingredients on the basis that they are inherently harmful or on the basis that they might lead people to think that these products produce certain health benefits.

Canada’s Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (Schedule 2) bans the use amino acids, caffeine, colouring agents, essential fatty acids, glucuronolactone, probiotics, taurine, vitamins and mineral nutrients. A different federal law, the Consumer Product Safety Act (CPSA) imposes a general prohibition on the manufacture or sale of products which are “a danger to human health or safety” and requires manufacturers to report adverse incidents. (Tobacco manufacturers are exempted from the requirements of this law).

The Tobacco Directive of the European Union requires member states to ban the use of vitamins, caffeine, taurine and other stimulants and colouring agents. Unlike Canada, the EU also bans the use of additives that have CMR properties (carcinogenic, mutagenic or reprotoxic) and requires that “ingredients may not pose a risk to human health in heated or unheated form.”

New Zealand prohibits the use of several chemicals in vaping liquids in its Smokefree Environments and Regulated Products Regulations 2021 (Schedule 5). These include a ban on carcinogenic, mutagenic, reprotoxic chemicals, those which have specific organ toxicities (STOT-RE, with exceptions for benzoic acid and nicotine salts), and other chemical categories.

Requirements for ingredient disclosure

No country is known to require e-liquid manufacturers to list all ingredients on the product labels, but some countries require manufacturers to provide governments with that information.

Neither consumers nor governments know the entirety of the ingredients of the e-liquids sold in Canada. There is currently no requirement for manufacturers to provide Health Canada with a list of ingredients in their vaping liquids and no obligations to identify the flavouring compounds on packaging. The federal Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations require manufacturers to provide consumers with limited information on e-liquid ingredients. If flavourings are included, the manufacturer need only indicate that they contain “flavour”. That said, Health Canada has signaled its intention to develop reporting regulations for vaping products since 2017, and more recent indications suggest/state that draft regulations might be published in winter 2022.

No provincial government requires vaping product manufacturers to provide ingredient list. British Columbia’s E-substance regulation requires that manufac

Nevertheless, in Canada some manufacturers voluntarily identify the presence of certain harmful ingredients. In packages for VUSE pods, BAT-Imperial Tobacco lists the presence of the toxic compounds (2-) hexanol (blueberry) and furaneol (strawberry).

In the European Union manufacturers of e-cigarettes must provide notification to governments 6 months before placing a product on market. There is an EU-wide common gateway for these reports. There is a standard reporting form which requires companies to provide details on each ingredient. Manufacturers are required to report on toxicity of ingredients and on the emissions produced.

In New Zealand, manufacturers must (by February 2022) provide notification of all products that they intend to sell, and they must report all adverse reactions. They must provide government with information on each chemical ingredient (name and amount).

Part 2. The chemicals that give flavour to e-cigarettes

Flavouring additives currently used Canada

Between 2017 and 2019, Health Canada purchased 825 samples of vaping liquids in major Canadian cities and analyzed these liquids using chromotography. This Open Characterization project was cited as background to the proposed flavour restrictions. [2]This analysis identified over 1,500 unique chemical compounds (a smaller number than the 400,000 compounds reported by the Vaping Industry Trade Association) . Many of these compounds appeared in a small number of products and only 4 compounds (nicotine, propylene glycol and glycerol and β-Nicotyrine) were found in more than half of the e-liquids. The chemicals detected were in a wide range of chemical families, with alcohol and organooxygen being the most common.

This study found that tobacco-flavoured e-liquids had somewhat fewer flavouring ingredients than did those marketed as fruit, mint-menthol, desert or confectionary. It also found significant variation over time, but whether this reflected differences in the e-liquids sampled or changes to the formulation was not made clear. Flavouring chemicals were also found in the “unflavoured” category, and the 5 most frequently detected flavour chemicals had sweetening properties (vanillin, ethyl maltol, ethyl vanillin, vanillin propylene glycol acetal and cyclotene).

Flavouring additives used in other countries

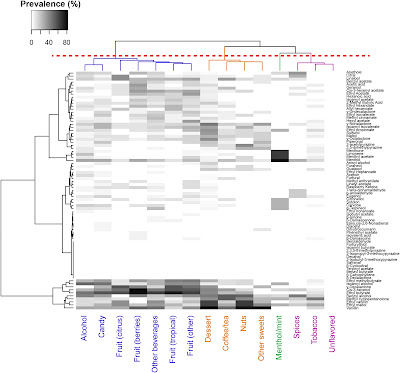

Because e-cigarette manufacturers are required to disclose their ingredients to governments in the European Union, it is possible to identify which compounds are most commonly used with which flavours. Analyses of e-cigarette ingredients been conducted on behalf of governments in Europe, including the Netherlands [3] and France [4]. For the almost 17,000 products reported to the Netherlands’ government, 213 unique flavouring compounds were identified, of which only 25 were found in more than 10% of the products. The most common flavouring chemicals used in tobacco-flavoured e-cigarettes were: Ethyl maltol, Methyl cyclopentenolone, Vanillin, 2,3,5-Trimethylpyrazine and Furaneol. For mint-menthol flavours, the 5 most common ingredients were: Menthol, Menthone, Ethyl maltol, Vanillin and Eucalyptol. The figure from Krusemann et al [5] below identifies the use of 79 chemicals in various flavour categories.

Part 3: The health effects of e-cigarette flavourings (including those Health Canada proposes to authorize)

Many e-liquids produce toxic compounds, some of which are not present in cigarette smoke

A number of reports have been published which raise concerns about the toxicity of e-cigarette ingredients, including flavourings. These include studies of e-cigarette liquids purchased in Ontario [6] which found that one fifth contained chemicals associated inhalation toxicity. this study found that 70% of e-liquids had measurable levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs). Health Canada’s subsequent study found no nitrosamines,[2] but did identify other compounds which are thought to cause cancer, including one (Naphthalene) which was found in 1 in 8 samples.

Toxicologists reviewing the evidence on the health effects of specific e-cigarette ingredients [7] express concern that although many e-liquid ingredients are thought to be safe as a food additive, little is known about what happens when they are inhaled. Also unknown are the toxic properties of the chemicals that are produced when flavouring and other e-liquid ingredients are combined and heated. With much left to be learned, it is nonetheless established that many flavouring ingredients used are known to be harmful. [8]

The French government recently reviewed the toxicity of e-cigarette ingredients, developing a priority list with 3 categories for regulatory consideration: (1) those which were known to pose significant risks, (2) those which were known to pose risks, and (3) those whose risks were not established. Fifty of the chemicals that manufacaturers had reported to government as used as ingredients or found in emissions were found to be cancer-causing, mutagenic, reprotoxic, endocrine disruptors, or toxic to specific organs.

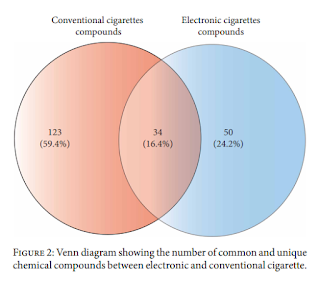

Health Canada and other governments have based their decision to liberalize the vaping market on their determination that vaping is less harmful than smoking, in part because “vaping products typically contain …lower levels of several of the harmful chemicals found in smoke”. Equally, however, vaping products typically contain several harmful chemicals that are not found in smoke: the systematic review cited earlier found one-quarter of the harmful compounds found in conventional and e-cigarettes were unique to e-cigarettes.[7]

Health Canada proposes to restrict flavourants on the basis of their attractiveness to youth, not on the basis of their harms to users.

As mentioned above, Health Canada is the first government to propose regulating the ingredients that will be allowed in e-cigarettes. This creates the potential to block the use of compounds that are known to be harmful. It also creates a more manageable set of ingredients for which health effects can be monitored. Health Canada will allow nicotine and 5 carrier agents and nicotine-modifiers (propylene glycol, glycerol, benzoic acid, citric acid, sorbic acid). It has identified 40 flavouring ingredients that will be permitted for tobacco-flavoured liquids and 42 for mint-menthol flavoured.

This list was created with the intention to “strike a balance between reducing the appeal of vaping products, to protect youth from inducements to use vaping products, and leaving some flavour options for adults who smoke and who have transitioned, or wish to transition, to vaping.” Consistent with this aim, the government proposes to prohibit the use of sugar and flavouring compounds that make e-liquids taste sweet (including commonly-used ingredients like Ethyl maltol and Vanillin).

The regulatory aim is not to make vaping liquids less harmful. Reflecting the absence this objective, the list of permitted flavourings includes chemicals that are known to be carcinogenic, mutagenic or reprotoxic, and that are not approved for use even in foods. These are Estragole, Furfuryl alcohol, Pyridine, Isophorone, Alpha-terpinene, Wintergreen oil, Para-cymene, Pulegone, Menthofuran, 4-ethylanisole and methyleneisophorone. Other ingredients on Health Canada’s list of authorized ingredients have been identified as the highest priority for regulation in France (including Benzoic Acid, Pyridine) and its second-highest (Propylene Glycol, Ethyl vinyl ketone, Butyric acid, 2-acetylpyridine, Alpha-terpinene, Nonanoic aacid, Glycerol, Thymol and Carvone).

Curiously, it was the Vaping Industry Trade Association which first drew public attention to the potential harms of these flavouring ingredients. In its brief to government, the major manufacturers want government to identify the chemicals that will be banned instead of identifying those that will be permitted. (Our submission recommended that the list of prohibited ingredients be expanded to include the acids which increased the addictiveness of these products by facilitating inhalation).

Part 4: Implications for public health

A. Provincial governments should not rely on timely federal measures to protect kids from enticingly flavoured e-cigarettes.

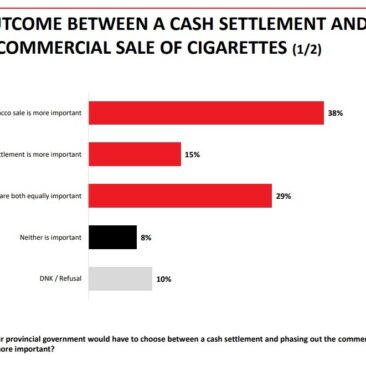

It is unlikely that Health Canada’s proposed flavour restrictions will survive without a significant fight, and the industry may be able to postpone implementation through legal and other tactics.

Because this new Canadian approach would set a world precedent and would denying the vaping industry access to an endless source of chemicals to create new flavourings, it will be fiercely opposed. Already this industry is lobbying fiercely to defeat and delay this measure. Because it is a novel regulatory approach, it is more vulnerable to legal and technical challenges. The Canadian Vaping Association reports it has raised $1 million in its legal fund. The “technical issues” raised by the Vaping Industry Trade Association seem to have already caused delays.

Those provinces and territories (and municipalities) which have not already banned e-liquid flavours should consider doing so soon.

B. Governments should limit flavouring ingredients in order to reduce the harms of vaping products

Flavourings in vaping liquids are harmful to young people who are encouraged by them to try an addictive product. (30% of Canadian vapers have never smoked cigarettes) [10]

For those who are using vaping products to reduce or end smoking vaping flavours unnecessarily add to harmful chemicals they will ingest with their nicotine dose. (One-third of Canadian vapers are former smokers and about 40% are dual users.) [10]

Because people interpret pleasant tasting compounds as safer, and less pleasant compounds as being more harmful, any flavouring that makes e-cigarettes “taste better” will also make it “seem less harmful.” Reducing or eliminating flavours will help consumers better comprehend the risks.

New labelling requirements, such as requiring full disclosure of ingredients and addidtional warning on flavoured products, would assist vapers in understanding how to reduce these risks if they wish to continue vaping.

A ban on flavourings in e-cigarettes that are sold as recreational drugs need not apply to vaping products which are approved as therapeutic products or smoking-cessation aids under the provisions of the Food and Drugs Act.

To protect the health of vapors, provinces and territories should adopt the most extensive flavour restrictions possible, including bans on mint-menthol flavours.

C. Governments should collaborate in developing ingredient standards for e-liquids.

Health authorities across the globe are faced with new regulatory challenges as a result of the introduction of vaping products and other novel nicotine devices.

Many vaping manufacturers operate globally. With their human and financial resources, their trade secrets and their willingness to challenge regulation, they have a significant advantage over national health regulators. This disadvantage can be somewhat addressed if regulators collaborate in understanding these new products and in developing a regulatory response to them.

Health Canada’s proposed regulation breaks important new ground, and implementing this approach will provide a precedent for other countries. European health agencies are using mandatory reports on ingredients and emissions to establishing a foundation for some ingredient controls.

Health Canada should accelerate ingredient restrictions by collaborating with European and other countries to identify chemicals which should be banned from e-liquids or their emissions because of their ability to induce young people to experiment, to facilitate addiction or to cause harm.