There are thousands of scientific studies on tobacco use published every month (37,000 so far this year!), but only a few find their way into the mainstream media. Among those, even fewer seem to have real influence on government policies.

In my circles, one of the most influential papers this year was a British study on the effectiveness of e-cigarettes at helping smokers quit. Psychologist Dr. Peter Hajek and his colleagues used the “gold standard” methods of a randomized clinical trial to compare E-cigarettes (consumer products) against NRT (licensed therapies) at as cessation products.

The results of this study were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January and immediately reported by media outlets across the world. Time magazine said the study showed “E-Cigs More Effective Than Nicotine Replacements in Helping Smokers Quit”, a messages echoed in many Canadian media outlets.

The idea that e-cigs are *twice as good at helping smokers quit* as NRT has now taken root.

Indeed, in some important quarters in Ottawa it seems to have become part of the tobacco control belief system. More than once over the past few months have I have heard this study cited as a reason that governments should continue to allow e-cigarette promotions.

Differing points of view

Yet Dr. Hajek and his team are not the only highly qualified researchers looking into this issue, and theirs is not the only scientific conclusion on offer.

Among other respected public health scientists who have looked at the efficacy of e-cigarettes as cessation products are those at the World Health Organization. This summer, after considering Dr. Hajek’s results and others, the WHO concluded:

Although some [Electronic nicotine delivery systems] have been shown to help smokers quit conventional smoking under certain conditions, when used as NRTs the scientific evidence is inconclusive. There have only been a limited number of randomized control trials and longitudinal studies investigating the role of ENDS as potential cessation aids offered to a population, and their conclusions are equivocal.

This is not the only time that Dr. Hajek and the World Health Organization have come to starkly different conclusions about interpreting research findings. In 2014, Dr. Hajek was among a research team which openly criticized the WHO, accusing it of “misleading” the public with the following statements: “Youth are rapidly adopting e-cigarettes”, “the hope that e-cigarettes will reduce harm by delivering ‘clean’ nicotine will not be realized in continuing dual users” and “E-cigarettes deliver lower levels of toxins that conventional cigarettes, but they still deliver some toxins.”

Nor is it the first time that Dr. Hajek has nailed his colours to the mast of e-cigarettes being so safe that their use should be promoted. He was part of the scientific team that advised Public Health England to promote the idea that the differences in harm between e-cigarettes and cigarettes could be quantified, and that the comparative measure was “95% safer”. Canada’s Heart and Stroke Foundation and The Lancet are among the many who have criticized the use of the “95% safer” claim.

A second look at the outcomes of Dr. Hajek’s experiment.

The data presented in the table below shows a broader range of outcomes from Dr. Hajek’s study, drawing data from the NEJM paper and also in a NIHR Health Technology Assessment report published in August, i.e.

- “The 1-year abstinence rate was 18.0% in the e-cigarette group, as compared with 9.9% in the nicotine-replacement group”.

- “Among participants with 1-year abstinence, those in the e-cigarette group were more likely than those in the nicotine-replacement group to use their assigned product at 52 weeks (80% [63 of 79 participants] vs. 9% [4 of 44 participants])”

- “19 participants in the NRT arm using NRT at 12 months …”

- “173 participants in the e-cigarette arm using e-cigarettes at 12 months… “

- “Among the e-cigarette arm abstainers, two were using non-allocated NRT at 12 months, whereas in the NRT arm, nine [abstainers] were using non-allocated e-cigarettes.”

(No information was found on the number of people who used both NRT and e-cigarettes. Even if they were some, the results presented below would not differ greatly.)

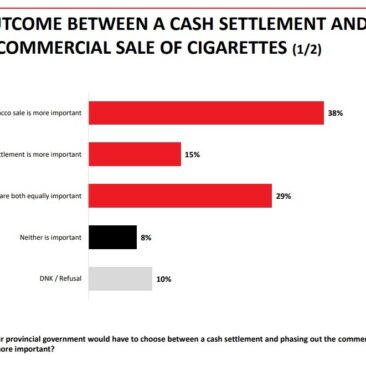

- Participants in the E-CIG group had almost double the success in stopping using cigarettes (18% vs 9.9%). This is as the media reported.

- Participants in the NRT group had more than double the success in ending nicotine use (7% vs. 3.2%). This is something the media failed to report.

- Participants in the E-CIG group had a much higher risk of becoming dual users (25.1% vs. 15.2%). This is something that the media also failed to report.

Other important conclusions can also be drawn from these outcomes:

- For people trying to beat nicotine addiction, failure continues to overwhelm success. This should heighten concerns about increase uptake of nicotine use.

- Those who have the opportunity to use e-cigarettes, including those who are encouraged to use NRT instead, are much more likely to both smoke and vape than they are to only vape. This might dampen enthusiasm that those who try vaping will be able to switch completely.

Higher standards of evidence

Single clinical trials, no matter how well performed or reported, are not usually considered the strongest evidence base for decision making. That distinction is usually reserved for systematic reveiws of multiple studies.

In 2016 two systematic reviews of e-cigarettes as cessation aids were conducted. They did not come to the same conclusion.

One was by the Cochrane reviews (and Dr. Hajek participated in this review.) This panel focused on the results of 2 randomized clinical trials, and concluded that “There is evidence from two trials that ECs help smokers to stop smoking in the long term compared with placebo ECs.” The quality of those studies was considered low, and Dr. Hajek’s 2019 results will likely strengthen this conclusion in subsequent Cochrane reviews.

The other was a systematic review and meta analysis conducted by U.S. physician Dr. Sara Kalkhoran and Dr. Stanton Glantz. They looked over the same literature field, and included the same 2 clinical trials as the Cochrane review had. In addition, they considered the results of 20 studies with control groups and other studies. The conclusions from this analysis were that rather than helping smokers quit, e-cigarettes made it harder for them to do so. The “odds of quitting cigarettes were 28% lower in those who used e-cigarettes compared with those who did not use e-cigarettes.”

A Canadian study involving more than 6,000 smokers was included in the Kalkhoran review, but not by the Cochrane team. It was conducted at CAMH, and eventually published both as a conference paper and as a journal article. Those would-be quitters who used e-cigarettes were less likely to succeed in quitting. “E-cig adoption seems to negatively affect cessation outcomes and provides no benefit as a harm reduction tool …”

This year researchers at the Ontario Tobacco Research Unit published a review of “E-Cigarette Use for Smoking Cessation.” They found “a wide range of results” and – while clearly open to the idea of using vaping as a cessation tool – nontheless reported that “In general, the scientific literature regarding the effectiveness of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid remains inconclusive.”

The Montreal Jewish General is leading a clinical trial on e-cigarettes as cessation devices, partnersing with several hospitals across Canada. Their results are not expected until next year.

Policy implications

Setting policy or clinical practice guidelines on the role of e-cigarettes is challenging in the messy real world of competing evidence, uncertainty, nuance and concious/unconcious bias. And that is before commercial influence and tobacco industry interference is added to the mix!

Currently, smokers who want to quit smoking have a variety of tools available to them, including a variety of licensed NRT therapies, non-licensed e-cigarettes, as well as proven and unproven behavioural supports that range from telephone counselling to hypnotherapy. None of the above has been the choice of most successful quitters.

Smokers (and those who pay for quitting programs) are entitled to know the benefits and the risks of the approaches on offer. In the case of e-cigarettes, Dr. Hajek’s paper is presented as evidence that E-cigarettes are a better option than NRT. The same paper also provides evidence that NRT is a better option for those who want to overcome addiction and also for those who want to avoid the additional risks of dual use.