This post reports on the results of data provided by Statistics Canada as a custom tabulation (purchased data extraction). The data cited in this post are linked at the bottom of this page, as are notes on concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on the 2020 survey results.

The CCHS Rapid Response module helped fill data gaps created by the termination of other surveys

The law to legalize vaping products in Canada was introduced to Parliament in 2016 and passed in 2018. The federal government did not, however, add questions about vaping behaviour to its major health survey (the Canadian Community Health Survey) until the 2021 cycle. This gap was made more significant by the decision of Health Canada to terminate the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drug Survey in 2017. These twinned decisions meant there was no national survey of vaping behaviour for the year before or the 18 months following legalization.

It was not until the fall of 2019 that Statistics Canada implemented the smaller-scale Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey. In addition, Health Canada commissioned a handful of questions on vaping as part of a “Rapid Response” module for the 2020 CCHS. Rapid Response modules are generally asked of a portion of the 60,000+ participants in the annual survey. The results are made available to the commissioning agency and to qualified researchers in an accelerated timeframe, but are not generally included in the regular data releases by Statistics Canada.

This module was in the field in January to March 2020, and September to December 2020. Results for 3 questions related to current, ever and daily use of vaping products (cross tabulated with smoking status) were provided to us last week by Statistics Canada as a custom tabulation. The sample size was not large enough to provide additional breakdown by age or province.

These results suggest that:

1. The drop in smoking results from a growth in the never smoking population, not an increase in quitting.

2. Legalizing vaping has not increased recent quitting rates.

3. Relatively few Canadian smokers (2%) are switching to vaping.

4. Most (71%) Canadian vapers are not reducing harm

5. Trying a vaping product results in daily use for 1 in 8 Canadians

6. Population turn-over has contributed to reductions in smoking rates.

1. The drop in smoking results from a growth in the never smoking population, not an increase in quitting.

1. The drop in smoking results from a growth in the never smoking population, not an increase in quitting.

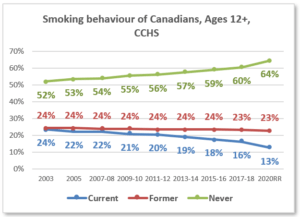

The drop in smoking that was measured by this cycle of CCHS was accompanied by an equivalent uptick in rates of never smoking. The rate of former smokers was essentially unchanged.

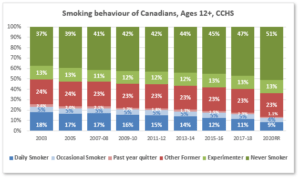

The customary 3-variable definition of smoking behaviour shows that the proportion of Canadians who are former smokers has barely changed over the past 15 years.

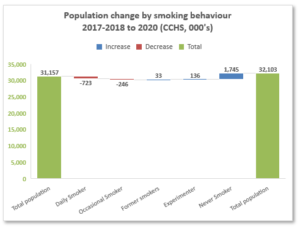

A display of results of full set of smoking behaviour variables (shown below) provides a more detailed picture of the extent to which never-smoking is driving the change in smoking rates. Between 2017-18 and 2020, the percentage of Canadians who had never smoked a single cigarette increased by 4 percentage points. The proportion who had experimented (smoked under 100 cigarettes) remained steady at 13%, as did the proportion who had quit smoking more than a year before the survey was taken (23%). The proportion of daily and occasional smokers fell by a combined 3 percentage points (from 16% to 13%).

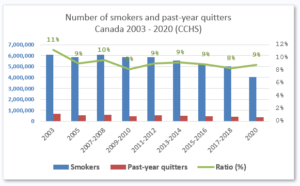

Smaller than in previous years was the proportion of the population that had quit smoking in the previous 12 months: 1.1% in 2020 compared with 1.3% in 2017-2018 and 2.6% in 2003. In absolute numbers, in 2020 there were 356,700 Canadians who said they had quit in the past 12 months compared with 414,900 average of 2017-18, and 679,900 in 2003.

Smaller than in previous years was the proportion of the population that had quit smoking in the previous 12 months: 1.1% in 2020 compared with 1.3% in 2017-2018 and 2.6% in 2003. In absolute numbers, in 2020 there were 356,700 Canadians who said they had quit in the past 12 months compared with 414,900 average of 2017-18, and 679,900 in 2003.

2. Legalizing vaping does not appear to have increased recent quitting rates.

From the perspective of encouraging smokers to quit, the CCHS results are no better than in previous cycles. The survey found a third of a million Canadians (357,000) had stopped smoking in the previous year, down from 414,900 in the annualized estimate of 2017-2018.

In absolute terms of people, this is less than in any other survey cycle, although when measured as a percentage of remaining smokers, it is consistent with historic trends.

In absolute terms of people, this is less than in any other survey cycle, although when measured as a percentage of remaining smokers, it is consistent with historic trends.

Relatively few Canadian smokers switch to vaping in a year.

Health Canada states that “potential public health benefits associated with reducing tobacco-related disease and death might be realized if adult tobacco users either quit or switched completely to vaping as a less harmful source of nicotine.”

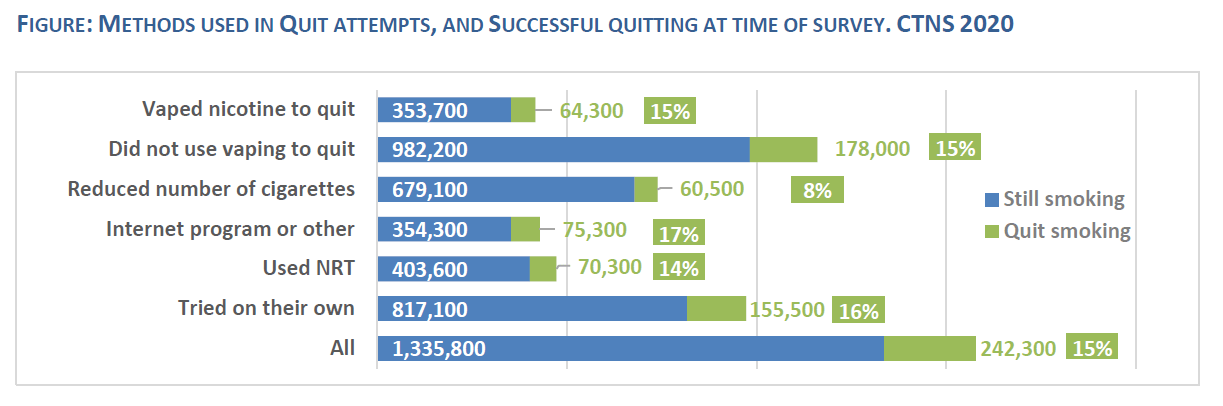

These CCHS results will have disappointed those who were hoping that the change in legislation would encourage smokers to switch to vaping products. In the year before the survey, relatively few smokers (68,500 of 4.1 million smokers, or 2%) transitioned from cigarettes to vaping. There were an additional 288,200 recent quitters who were not vaping at the time of the survey.

These CCHS results will have disappointed those who were hoping that the change in legislation would encourage smokers to switch to vaping products. In the year before the survey, relatively few smokers (68,500 of 4.1 million smokers, or 2%) transitioned from cigarettes to vaping. There were an additional 288,200 recent quitters who were not vaping at the time of the survey.

One fifth of those who said they had stopped smoking in the past 4 years were vapers (206,100 of 1.1 million former smokers). This time period which coincides with the period when legislation to legalize vaping was introduced.

The CCHS estimate of the number of past-year smokers who vape is consistent with the results of the 2020 CTNS, which found about 64,300 Canadian smokers used vaping to quit and were not smoking at the time of the survey. Because the CCHS had also asked about methods used to quit, the results suggested that those who used vaping products when trying to quit were no more likely to succeed than those who tried to quit using other methods.

3. Most (71%) Canadian vapers are not reducing harm.

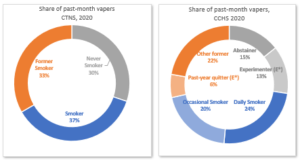

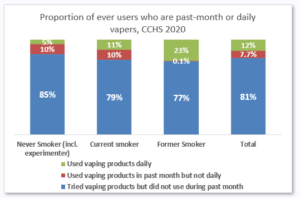

The 2020 CCHS Rapid Response module identified 1 million Canadians who vaped in the past month and 653,100 who did so on a daily basis.

Among past-month vapers, fewer than one-third (308,900) were using these products in a way Health Canada considers to reduce harm, in that they had once been smokers but no longer were. Virtually all of these were daily vapers (306,900), representing less than one-half of that total.

More than two-thirds of vapers had either never smoked at all (15%), had only experimented with cigarettes (13%), were also smoking either on an occasional or daily basis (20% and 24%). For these Canadians, the use of these products is not held by Health Canada to reduce harm.

More than two-thirds of vapers had either never smoked at all (15%), had only experimented with cigarettes (13%), were also smoking either on an occasional or daily basis (20% and 24%). For these Canadians, the use of these products is not held by Health Canada to reduce harm.

These results were very similar to those of the 2020 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey.

4. Trying a vaping product results in daily use for 1 in 8 Canadians

According to this survey, almost 5.6 million Canadians have ever tried a vaping product, which is 17% of the population surveyed. Of these, 1 million are past-month users (3.4% of all Canadians, and 19% of ever-users), and 653,100 vape on a daily basis (2% of all Canadians and 12% of ever-users).

The likelihood of becoming a daily vaper is very different for those who have never smoked than for those who have. While the estimates are qualified with coefficients of variation so large that caution is required, they suggest that 1 in 20 never smokers who tried a vaping product was a daily user in 2020, compared with 1 in 10 smokers and 1 in 4 former smokers.

The likelihood of becoming a daily vaper is very different for those who have never smoked than for those who have. While the estimates are qualified with coefficients of variation so large that caution is required, they suggest that 1 in 20 never smokers who tried a vaping product was a daily user in 2020, compared with 1 in 10 smokers and 1 in 4 former smokers.

This high retention rate makes vaping an attractive proposition for commercial businesses. Not surprising then that vaping companies give away free samples of their products.

5 Population turn-over contributes to reductions in smoking rates.

The Canadian population covered by this survey grew by almost 1 million people between the 2017-2018 cycle and 2020 (from 31.2 million to 32.1 million Canadians aged 12 years or older). This growth included a gain of 1.7 million more Canadians who report that they have never smoked 1 cigarette, 136,000 more who have smoked between 1 and 100 cigarettes (but don’t smoke now) and 33,000 more Canadians who say they used to smoke, but no longer do. Those population increases were off-set by a decrease of 968,000 smokers.

Recently-released results of the Canadian Census shed light on some of the underlying population changes. Four-fifths of the population growth in Canada in this period was the result of immigration, and not due to births and deaths. Immigrants are much less likely to have ever smoked than native-born Canadians. Both smokers and former smokers die sooner than do never smokers, so deaths also contribute to boosting the proportion of never-smokers in the country.

Recently-released results of the Canadian Census shed light on some of the underlying population changes. Four-fifths of the population growth in Canada in this period was the result of immigration, and not due to births and deaths. Immigrants are much less likely to have ever smoked than native-born Canadians. Both smokers and former smokers die sooner than do never smokers, so deaths also contribute to boosting the proportion of never-smokers in the country.

In short, a major reason that a smaller percentage of Canadians smoked in 2020 than in 2017-2018 is because more smokers left the population (died) and more never-smokers joined it (through immigration or aging). For every 30 fewer smokers that were counted in 2020, only one additional former-smoker was added to the population estimate.

NOTES

Differing surveys produce different estimates:

The reliability of a health survey can be affected by many factors — especially when it depends on the public being willing to answer the phone and answer questions truthfully.

The different results provided by the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey and the Canadian Community Health Survey illustrate that even when the same surveyors use the same questions of the same population, different estimates can be produced.

How many smokers were there in Canada in 2020?The CTNS reported 3.2 million of a population of 31.3 million aged 15+ (10.3%).The CCHS reported 4 million of a population of 32.1 million aged 12+ (12.6%)

How many vapers were there in Canada in 2020?The CTNS reported 1.46 million of a population of 31.3 million aged 15+ (4.6%)The CCHS reported 1.08 million of a population of 32.1 miillion aged 12+ (3.3%)

How many nicotine users were there in Canada (vapers and/or smokers) in 2020?The CTNS reported 4.15 million Canadians either smoked or vaped (or both) of a population of 31.3 million aged 15+ (13.3%)The CCHS reported 4.64 million Canadians either smoked or vaped (or both) of a population of 32.1 million aged 12+ (14.4%)

Definitions:

The categories of smoking behaviour used in the CCHS that are identified in this summary include:* Daily Smoker: someone who smokes on a daily basis* Occasional Smoker: someone who identifies as a smoker, but does not smoke daily.* Current smoker: someone who smokes on a daily or occasional basis* Past year quitter: someone who has smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime, but stopped doing so within the past year* Other Former Smoker: has smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime, but stopped doing so more than a year ago* Former smoker: someone who has smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime, but no longer smokes.* Experimenter: has smoked between 1 and 100 cigarettes, but does not currently smoke.* Abstainer: Has never smoked a cigarette* Never smoker: someone who has never smoked 1 cigarette or who has smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes.

Comparability of the 2020 CCHS survey results

COVID-19 resulted in a number of changes to the way CCHS data was collected in 2020. The survey was not conducted during the summer months, as it would normally would have been. The portion of the survey conducted in person was replaced with telephone interviews, meaning that Canadians no longer had to look the interviewer in the eye as they reported on their health habits. The survey had captured more Canadians with higher education and homes than in previous cycles. As discussed here earlier, all of these methodological adjustments could be expected to somewhat depress measures of smoking. The agency has warned that: “users are advised to use the CCHS 2020 data with caution.”

These cautions should be kept in mind when reviewing the data presented above.

Data sheets:

Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey Rapid Response 2020.Fact sheet.Excel sheet provided by Statistics Canada.

E-cigarette and tobacco use. Insights from the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey.Wave 1: 2019;Wave 2: 2020