Last week viewers of the American College of Cardiology’s virtual annual scientific session were able to see the initial results of the first large Canadian randomized clinical trial of e-cigarettes as a cessation device. Thanks to the ACC’s sharing of this event and Youtube technology, a 6-minute synopsis of his presentation is available to all.

In short, this study found that after 12 weeks of treatment, those who used e-cigarettes with nicotine to quit smoking were twice as likely to be cigarette-free at the end of treatment as were those who received only counselling. Data on longer-term outcomes are still being collected.

The E3 Trial

Dr. Mark Eisenberg of McGill University heads the only registered Canadian randomized clinical trial (RCT) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of electronic cigarettes as cessation devices. The “Evaluating the Efficacy of E-Cigarette Use for Smoking Cessation (E3) Trial was first registered with the international database of clinical trials in 2015 with the following purpose:

The Evaluating the Efficacy of E-Cigarette Use for Smoking Cessation (E3) Trial will be the first large trial to address the important issue of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation in Canada. The trial will randomly assign participants to receive nicotine e-cigarettes and minimal counseling, non-nicotine e-cigarettes and minimal counseling, or only minimal counseling for 12 weeks. Participants will then be followed for one year to see which (if any) group is more likely to have quit or reduced their smoking. Information about potential side effects and safety will also be collected. The E3 Trial will provide law-makers and the public with important information about the use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation.

This experiment was designed to measure how many people had stopped smoking after one year (7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at 52 weeks). Although many quit attempts fail after the one-year mark, this is the time frame commonly used to measure successful long-term quitting. The study also aimed to identify how many cigarettes were smoked by those who didn’t quit, any adverse effects and whether or not participants had occasionally relapsed during the trial (“continuous abstinence”).

The Canadian Institutes for Health Research was a major funder of the project, providing $1.1 million for the study between 2015 and 2019.

Dr. Eisenberg’s early results

Dr. Eisenberg found that e-cigarettes with nicotine when used with counselling were twice as effective as counselling alone, and that 1 in 5 would-be quitters who used e-cigarettes with nicotine had stopped using cigarettes after the 3 month treatment period, compared with 1 in 10 among those who received only counselling.

The study was cut short after Dr. Eisenberg and his team experienced “prolonged delay in e-cigarette manufacturing.” Although the primary endpoint was moved back from 52 weeks to 12, Dr. Eisenberg explained that he will be following study participants and will report on their smoking behaviour at the one-year mark.

How do Dr. Eisenberg’s results compare with other trials of e-cigarettes?

In its description of the study design published last month Dr. Eisenberg’s team provides an up-to-date summary of the issues and evidence surrounding e-cigarettes as cessation devices, including an Appendix which identifies previous studies.

These include:

- 2013 study in New Zealand finding 7.3% quitting among e-cigarette users at 6 months

- 2013 study in Italy among smokers not intending to quit.

- 2016 study of young adult smokers in the USA who were not intending to quit.

- 2017 study of smokers in the USA who were not intending to quit.

- 2018 study of adult smokers in the USA some of whom received free e-cigarettes in addition to usual care but did not quit in higher numbers.

- 2018 study of lung cancer screening patients in Italy where 25% of those who received e-cigarettes were abstinent at 12 weeks.

- 2019 study of adult smokers using the UK stop smoking services of whom 18% were abstinent at 1 year.

- 2019 study of men in South Korea among whom 65% were abstinent at 12 weeks (as were the NRT group).

- 2019 study of smokers in New Zealand of whom 35% of those who received both patches and e-cigarettes were abstinent at 6 months.

The variety of results in these studies point to the challenges identified by the Surgeon General this spring – with so many different types of e-cigarettes on the market – a heterogeneous market — it is more difficult to make scientific determinations about what works and what doesn’t.

The e-cigarette used in Dr. Eisenberg’s study was manufactured by NJOY and was developed as a standardized research e-cigarette. How it compares with JUUL, or Vype or other products on the market — which have higher amounts of nicotine and which use salts to boost delivery — is a whole other research issue.Importantly, in his video presentation, Dr. Eisenberg was not bullish about his results. While he said the results were “very very good” he also cautioned “There’s no question that e-cigarettes are not a magic bullet for smoking cessation. It’s much better than counselling alone, but even so we are looking at almost 80% of individuals who are still smoking to some extent at 12 weeks.”

How do Dr. Eisenberg’s results compare with results from trials of other stop-smoking treatments?

Over 1,400 trials for smoking cessation methods have been registered on the clinical trial database, including several dozen in Canada. These studies have been reviewed by leading scientific panels, including:The Cochrane Review, which has come to many conclusions about the comparative effectiveness of stop-smoking methods. In their recent advice for cessation during the COVID-19 pandemic, however, they excluded e-cigarettes from the recommended methods “as the risks associated with their use in relation to the current pandemic are not clear.”

The U.S. Surgeon General’s office, which recently published a special report on Smoking Cessation this past January. Within it is a 50-page review (Chapter 6) of the evidence behind interventions. While finding that “the evidence is inadequate to infer that e-cigarettes, in general, increase smoking cessation” the USSG noted that the evidence was “suggestive” that e-cigarettes with nicotine were more effective than those without.When Health Canada approved varenicline as a smoking cessation drug in 2008, it did so based on clinical trials that found that at the same 12-week point in the trial, abstinence rates with varenicline were 44% and for buproprion were 30%. These appear to be much higher success rates than Dr. Eisenberg found with e-cigarettes.

What might Dr. Eisenberg’s results mean for health regulators?

Clinical trials are most often used by health regulators when deciding whether or not to permit a drug for sale, whether to pay for it with drug-plans and whether to encourage its use as part of clinical practice.Although e-cigarettes are already for sale as recreational products in Canada, they are not licensed as therapeutic medicines and, as far as we know, no manufacturer has requested that they be so. Because such permissions are product-specific, Dr. Eisenberg’s study will not likely affect any such decision. Only manufacturers whose devices have been approved in this way may market e-cigarettes as cessation products.

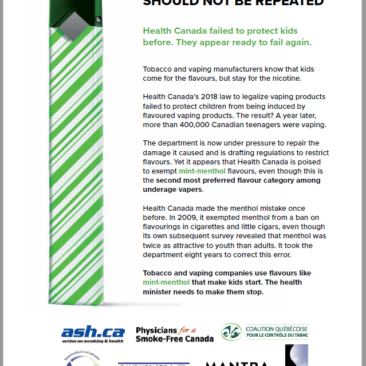

Even without their registration as therapeutic products, Health Canada appears interested in the use of e-cigarettes as cessation device. It currently encourages smokers to use e-cigarettes to stop smoking cigarettes, and recently explored how to support health care providers to “have meaningful discussions with their patients about smoking cessation and alternative nicotine products.”

The policy issues around e-cigarettes as cessation products are made more complex by different understandings of what “cessation” means. Some use it to describe switching from cigarettes to e-cigarettes. Others – including three quarters (77%) of the health care providers polled by Health Canada — feel that successful quitting means ending nicotine use, not continuing to use an alternative product.

Results from Statistics Canada’s recent survey on smoking and nicotine use, the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, already show that one-third of those using e-cigarettes are doing so as a way of cutting down or quitting. The survey asked Canadians which quit methods they had tried. The results, once released, will add to our understanding of how likely quitters trying this method are to stop using cigarettes, or how vulnerable to increasing their health risks through dual use.

There is another Canadian RCT with information on e-cigarettes and cessation

Another CIHR-funded RCT on smoking cessation focused on the effricacy of smart-phone app on young adult quit rates. As a secondary analysis, data from this trial was used to assess the experience of those who used e-cigarettes throughout the 6 month trial (persistent users), compared with those who were found using them only at the beginning or end of the trial (transient users) and those who did not use them at all (non-users).

While the study has not apparently been published, the results were published in a 2017 Master’s Thesis by Arti Saxana They were also the subject of a web-cast presentation by Dr. Bruce Baskerville last year.

In this study, at the 6 month mark, those who had not used e-cigarettes were twice as likely to have been been abstinent from cigarettes for a month.