Last week BAT/Imperial Tobacco Canada began selling the disposable vaping device Vuse Go in Canada.

From the advertising copy on its website, it appears that this new product is being used to recruit new users: “Whether you are new to vaping, want to try some new flavours without committing, or simply aren’t sure which device is right for you, disposable vapes could be the option for you!” (The launch is also supported by a Youtube advertisement.)

From the advertising copy on its website, it appears that this new product is being used to recruit new users: “Whether you are new to vaping, want to try some new flavours without committing, or simply aren’t sure which device is right for you, disposable vapes could be the option for you!” (The launch is also supported by a Youtube advertisement.)

No surprises here.

Although PMI’s move to disposable vapes this summer took some by surprises, the launch of Vuse Go in Canada has been foreshadowed for months:

- This summer, BAT’s largest competitor – Philip Morris International – had chosen Canada as the first market for its disposable, Veeba.

- BAT had already introduced disposable vapes to its other top vaping markets: beginning in May in the United Kingdom, quickly spreading to France (as Vuse PUFF), Germany , Greece , New Zealand, Spain and likely other places. (The product will not likely be sold in the USA in the near future, as the U.S. Food and Drug Authority requires new brands of e-cigarettes to be inspected and authorized before being allowed on the market.)

- BAT had registered 6 versions of the Vuse Go trademark in Canada in the spring (Vuse GO, Vuse GO XL, Vuse GO Pro, Vuse GO Ultra, Vuse Go Max, Vuse Go Extra.

- BAT’s CEO had informed investors this summer that the marketing of disposable vapes was being done at an accelerated pace: “We launched Vuse Go our new disposable product in the UK in May. Taking just six months, this is our fastest speed to market launch yet and a great example of our increased speed and agility.”

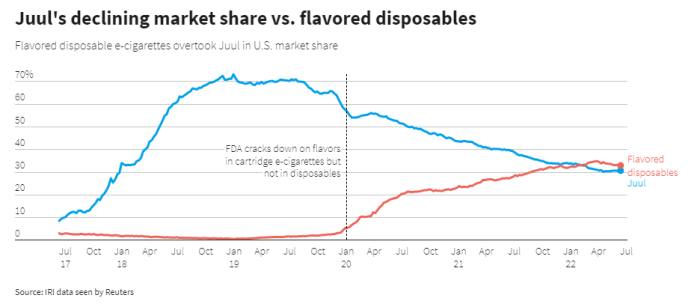

Move over, JUUL. Disposables are the next big thing.

|

| Reuters data cited in the Financial Times |

Recent reports from Great Britain and the United States have tracked a dramatic increase in the use of disposable cigarettes by younger people.

As U.S. state governments describe it, the wave of youth vaping that started in 2017 was a result of the product design and marketing of JUUL. Facing lawsuits and regulatory pressure, JUUL was forced to modify its business practices. The JUUL wave, from an investor’s perspective at least, has crashed – but not before it mapped out a path to profits for its imitators.

Just as the first generation of youth vapers were drawn in by JUUL and its imitators, their younger siblings are being hooked by disposable vapes. This next generation product is even more youth-friendly than JUUL: no-charging means greater convenience and no incriminating paraphernalia, low-price means less pain if confiscated and more ability to share with friend. Like JUUL before them – and unlike previous cig-a-like disposables – these new vapes have the cachet of being the latest teen fad. But like JUUL — and unlike fidget spinners — this is a teen fad that can leave lifelong consequences.

As affordable as fast-food.

These disposable devices are as affordable to young people as a meal at a fast food restaurant: the Vuse GO costs about the same as a McDonald’s Big Mac Meal ($12.19).

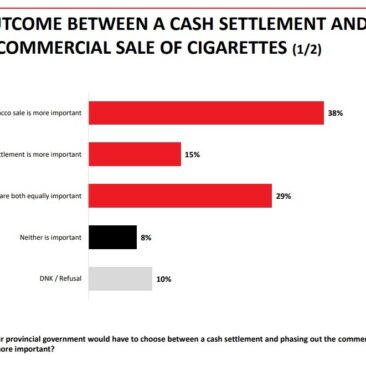

The $12.99 price includes the federal excise tax of $1.00, which took effect at the beginning of October. This tax was intended to help curb youth vaping, but without any complementary price regulations to ensure a minimum price or to prevent the manufacturers from altering prices to diminish the effect of the tax.

The $12.99 price includes the federal excise tax of $1.00, which took effect at the beginning of October. This tax was intended to help curb youth vaping, but without any complementary price regulations to ensure a minimum price or to prevent the manufacturers from altering prices to diminish the effect of the tax.

Other tobacco companies are selling disposable vapes at even lower prices. The introductory price of PMI’s Veeba was $9.99 – but this week – perhaps in response to the introduction of Vuse GO – the price was lowered to $5.99.

As tasty as food treats

But with harms that could go beyond addiction

One of the challenges of establishing the impact of vaping products has been the range of devices and liquids that are used, and the absence of a standardized dose that can be analyzed. Disposable vapes, however, are a standardized product and allow reliable analysis to indicate the chemicals to which a vaper is exposed. Studies of popular American disposable products (Puff Bar) have found excessive levels of harmful chemicals, particularly those used to produce ice flavours and have raised concerns about respiratory cancer risks.

The chemical profile of Vuse Go aerosols is not public. Tobacco companies are required by Canadian law to report on the quantities of certain toxins in the emissions from cigarettes, but the government has decided against imposing this requirement for electronic cigarettes.

Disposable, yes – but toxic waste too.

Disposable vaping products intensify concerns about the environmental damage of tobacco and nicotine products. Because of the harmful chemicals in the batteries and liquids, U.S. government agencies urge vaping devices and equipment to be treated as toxic waste.

A recent investigation by British journalists concluded that the quantity of disposable vapes thrown away in the UK each year contained enough lithium to make roughly 1,200 electric car batteries.

Sensitive to these concerns, BAT/Imperial promotes its “Vuse Take Back” system, and encourages disposable products to be discarded through a “responsible disposal program.” To participate in this program, consumers are told they can return their Vuse ePod devices in person to one of two stores (Toronto and Edmonton). As for the disposables — that is not yet in place (it is promoted as “coming soon”.)

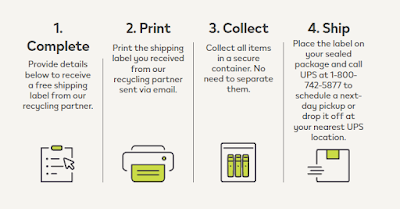

In the case of VEEBA, a disposal system for returned products has been implemented by RBH, albeit one that requires some organization and effort by consumers. To participate in this system, consumers must order and print a shipping label, package the used products and schedule a pick up for shipment.

|

| PMI/RBH instructs consumers on how to dispose of their Veeba devices. |

New challenges for health regulators …

In some countries, disposables have entered the market through cracks in health regulations or weaknesses in enforcement systems.

It was the U.S. ban on flavourings in JUUL-style products (and uncertainties about the status of synthetic nicotine) that became a springboard for disposable products like Puff Bar. In the United Kingdom, enforcement did not prevent the marketing of vaping products which broke U.K. regulations on maximum levels for nicotine and liquid volume. Denmark has also found that disposable vapes are being sold in defiance of its ban on flavoured liquids.

These experiences demonstrate new challenges facing health regulators as a result of increasing innovation in the nicotine market. A recent review of market trends concluded . The author of a recent review of market trends concluded “These challenges will increase as the tobacco industry continues to diversify its product portfolio, and weaponises ’tobacco harm reduction’ rhetoric to undermine policies limiting marketing, promotion and taxation of tobacco, nicotine and related products.”

… Prompting new regulatory actions

A number of governments have moved to better protect young people and the environment from the marketing of disposable vaping products:

- Last year, the Belgian government indicated its intention to ban disposable vaping products. In the face of trade challenges, the measure has been deferred, but the government says it intends to pursue it.

- Last week, the Irish Minister of State proposed a ban on disposable vaping devices, possibly as a component of bans on single-use plastics.

- This fall, Denmark has established an inter-ministerial “control task force” to address disposable e-cigarettes that were entering the market in defiance of the ban on flavoured vaping liquids.

- In September, Switzerland disclosed that it is considering putting a surtax on disposable devices.

- Earlier this month, the U.S. FDA has increased its enforcement efforts against Puff Bar and other manufacturers of similar disposable products.

- In April, the French territory of New Caledonia banned the importation of disposable e-cigarettes.

- In addition, 30 countries aim to protect public health by not permitting the sale of any vaping products, and 8 countries have moved to ban flavourings other than tobacco-flavour or tobacco and menthol.

Health Canada has signalled its intent to curtail flavourings, with draft regulations proposed in the early summer of 2021. In its forward regulatory plan of 2021, the department also identified the need to “impose restrictions on design features that are appealing to youth to prevent their use in the manufacture of vaping products.” There has been no update on the timetable for flavour restrictions, and plans for design regulations were dropped in the spring 2022.

How will we know if disposables cause problems in Canada?

Federal government surveys of vaping behaviour (like the Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey, the Canadian Community Health Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey) are not designed to monitor the impact of device or brand on consumer behaviour, or to provide quantitative evidence to support policy or regulatory adjustments related to these aspects. They will not track the use of disposable vapes by Canadian youth or adults. (Health Canada’s Canadian Cannabis Survey, by contrast, does ask questions about the use of disposable devices).

Other consumer research commissioned by Health Canada has on occasion provided qualitative insights into the impact of product design. For example, a study by Environics, made public this fall, concluded that “It was notable that, among youth – many of whom were still in high school – many either used disposable vapes such as Ghosts, or would share vaping devices with friends” … “Participants appreciated their compact nature, the variety of flavours available and their affordability compared to larger vapes, for which pods had become expensive. A few also explained that the nicotine concentration is higher in smaller devices, and they generally taste better.”

Implications for public health

Big Tobacco’s involvement in the disposable vape business exposes several vulnerabilities in Canada’s public health approach to nicotine:

Canadian regulators appear unconcerned or unprepared. Although the increased use of disposable vaping products has raised concerns and prompted new actions in other countries, Canadian federal and provincial health regulators have so far been silent about this development.

Our core health surveillance tools are not designed to assess the impact of specific products. Unlike the U.S. PATH study, Canadian government surveys do not follow the smoking trajectories of individuals (they are not longitudinal), and they do not gather information on the products used.

Canada has no protective barriers to market access. Unlike the European Union, Canada does not require pre-notification of the introduction of vaping products. Unlike the United States, Canada does not require vaping product manufacturers to receive authorization for new devices or brands.

Canada’s regulatory system does not provide a timely response to tobacco market developments. Unlike other health protective laws, the federal tobacco law does not authorize the government to implement interim regulations or otherwise reduce the time to respond to urgent concerns. (Three of the 5 tobacco- and vaping-related regulations currently in development were launched more than 5 years ago).

There are no health-protective controls on nicotine prices. Despite the evidence establishing the benefits of higher prices in reducing smoking (and other drug use), governments have been reluctant to impose price controls on tobacco or nicotine products. Taxation helps elevate prices, but does not prevent companies from selling below the cost of production to recruit new users to addictive products.