The updated Cochrane review of e-cigarettes — and what it should mean for Canada

Last week, the UK based health charity, Cochrane, released its sixth report on the evidence on the use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. This post reflects on how this and other Cochrane conclusions could serve Canadian efforts to reduce smoking at the population and individual levels.

In brief:

1) Cochrane establishes that in clinical trials, E-cigarettes fail 10 times more often than they succeed (roughly the same as NRT). Other reviews have shown that in real life they are even less successful.

2) The products used in the studies reviewed by Cochrane are different than those on the market in Canada. The U.S. Surgeon General recommends that because of the wide variation in products and usage it is not prudent to draw generalized conclusions about their efficacy as stop-smoking medications.

3) Cochrane reviews show that other stop-smoking medications do better in clinical trials. (The ones that, unlike e-cigarettes, have been assessed and authorized on the basis of their safety, efficacy and quality.)

4) Any advice to a smoker to use e-cigarettes to quit smoking (or to reduce the harms from continued nicotine use) should be tailored to individual circumstances and be individually delivered in a therapeutic context. Population-level encouragements for smokers to use e-cigarettes are imprudent. To date these have back-fired in Canada, resulting in more new nicotine addicts than former smokers.

Next verse, much the same as the first…

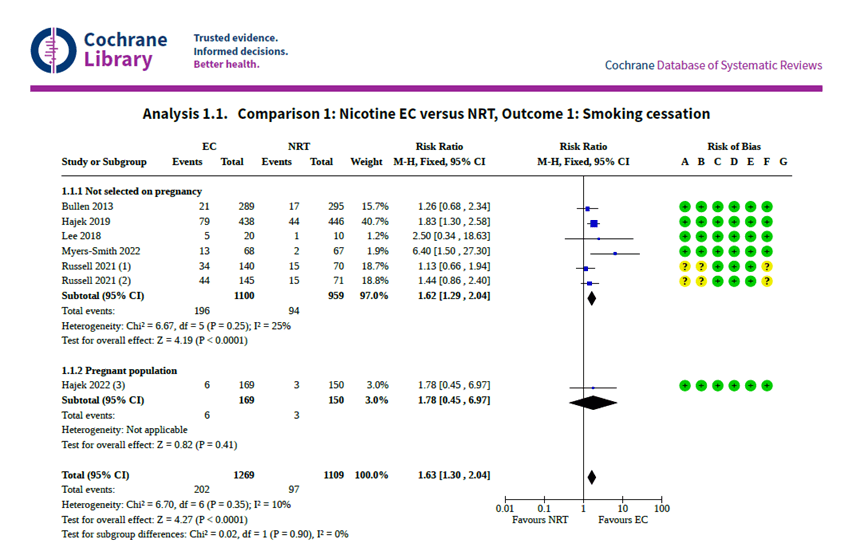

The Cochrane review on e-cigarettes that was published last week has the same central messages as the versions published in September 2021, the one published in April 2021, and the one published in October 2020. A major difference with earlier versions is the number of studies they accepted for their analysis: three that compared NRT to e-cigarettes were included in 2020, four in 2021 and six this year.

This study was released with considerable fanfare and extensive public relations efforts. Cochrane publishes several reports on tobacco issues (described at the end of this post) – few seem to get the same PR effort.

The press releases that accompanied the release of this update were clearly designed to encourage e-cigarette use by smokers. The lead author’s statement linked to the release of the report, suggests that e-cigarettes are highly effective at helping smokers quit: “For the first time, this has given us high-certainty evidence that e-cigarettes are even more effective at helping people to quit smoking than traditional nicotine replacement therapies, like patches or gums.”

Another coordinated press release was sent by well known e-cigarette enthusiasts. Professor John Britton presented e-cigarettes as a panacea for smoking cessation: “All smokers should therefore try vaping as a means to end their dependency on smoking tobacco.” (The release made no mention that Dr. Britton has been engaged by Canadian commercial vaping interests to oppose flavour restrictions in New Brunswick.)

There are many reasons to disagree with these views.

Cochrane has confirmed that in clinical trials e-cigarettes are NOT very effective at helping smokers quit.

The reviewers memorably present their conclusions in a plain language summary: “For every 100 people using nicotine e‐cigarettes to stop smoking, 9 to 14 might successfully stop, compared with only 6 of 100 people using nicotine‐replacement therapy, 7 of 100 using e‐cigarettes without nicotine, or 4 of 100 people having no support or behavioural support only.”

Rather than confirm the superiority of e-cigarettes, these numbers confirm the inadequacy of both vaping products and NRT – even under the best of supervised therapeutic circumstances.

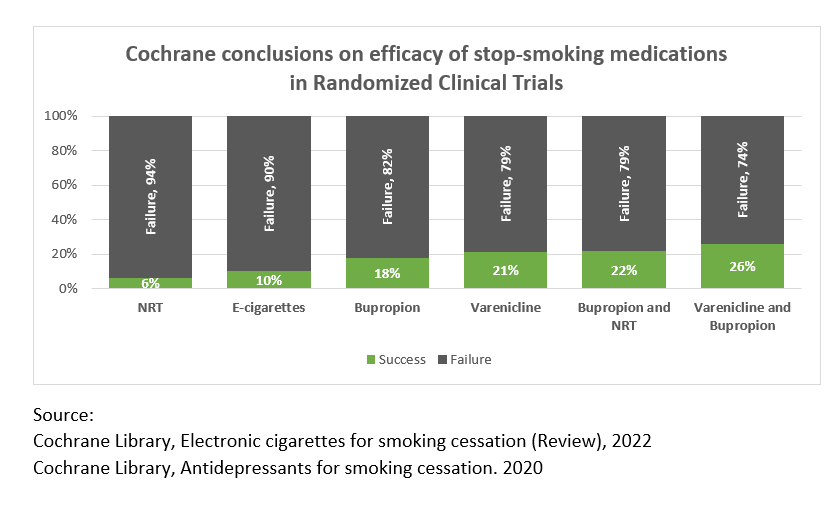

The Cochrane report on e-cigarettes concluded in effect that 90 of 100 smokers who use e-cigarettes to quit smoking will be smoking again within 6 months, compared with 94 failures for every 100 who use NRT.

The relative risk for success between E-cigarettes and NRT is 1.63 (10 vs 6 successes per 100 tries). The relative risk for failure between NRT and E-cigarettes is 1.04 (94 vs 90 failures per 100 tries)

(Simon Chapman provides a good discussion of the high rate of failure in his blog “Would you take a drug that failed with 90% of users? New Cochrane data on vaping “success”.)

Cochrane has confirmed that in clinical trials other stop-smoking medications available in Canada do better than e-cigarettes.

Other Cochrane reviews have assessed the effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation. These include the stop-smoking medications that have been approved by Health Canada following a review of their safety, efficacy and quality. (The safety, efficacy and quality of e-cigarettes is not examined by Health Canada before they are permitted for sale).

Among these medications are prescription medications Varenicline and Bupropion. These drugs do not replace nicotine from tobacco, but instead help the smoker end nicotine addiction by altering the brain’s response to it. Varenicline reduces nicotine withdrawal symptoms and diminishes the rewarding effects of cigarettes. Through a different mechanism, Bupropion also decreases nicotine withdrawal symptoms and may diminish the rewarding effects of cigarettes. Other over-the-counter stop-smoking medications authorized for sale include the natural health product Cytisine and the prescription anti-depressant Nortriptyline.

A 2020 review by Cochrane looked at the effectiveness of some pharmacotherapies, using similar analytic methods to those used in the review on e-cigarettes. This review concluded that for every 100 people who tried to quit smoking:

▪ 17 to 20 were successful at quitting for at least 6 months if they used Bupropion alone (80 to 83 failed).

▪ 17 to 28 were successful if they used Bupropion and NRT (72 to 83 failed).

▪ 21 were successful if they used Varenicline alone (79 failed).

▪ 20 to 33 were successful if they used Varenicline and Bupropion (67 to 80 failed).

Cochrane’s conclusions on efficacy of stop-smoking medications are displayed below:

Randomized Clinical Trials are designed for therapeutic medication and are not the right yardstick to assess consumer product use.

In developing its assessment of the effectiveness of e-cigarettes as cessation devices, the Cochrane reviewers considered only clinical trials that used randomized control trials (RCT). This may be the gold standard for assessing medications before granting licensing approval, but it does not reflect the reality of most smokers’ quit attempts.

In RCT’s, smokers are engaged and participating in a therapeutic cessation attempt, often using a specified e-cigarette product. In the real world, most try to quit without any external structure or support and use a variety of products.

Stan Glantz provides a good discussion of why Randomized Control Trials are not the best method for assessing stop-smoking products that are not sold as medicines.

This Cochrane review is out of step with other scientific assessments of the usefulness of e-cigarettes as quitting aids.

The Cochrane reviewers are only one of several research groups conducting systematic reviews of e-cigarettes efficacy for smoking cessation. Even among reviews that, like Cochrane, considered only Randomized Control Trials, other scientists have concluded that even on the narrow question of whether e-cigarettes are superior to NRTs, the evidence is not there.

Reviewers of RCT’s on e-cigarettes who came to different conclusions include:

- An Australian review of RCT’s found limited evidence that in the clinical setting freebase nicotine e-cigarettes are efficacious as an aid to smoking, and that they double the likelihood of relapse to resuming smoking, strong evidence that e-cigarettes increase combustible smoking uptake in non-smokers and insufficient evidence that nicotine e-cigarettes are efficacious outside the clinical setting. (Banks et al, 2022)

- An Irish review of RCT’s found “no clear evidence of a difference of effect” between e-cigarettes and NRT. (Quigley et al. 2021

- A review for the US Preventive Services Task Force found “inconsistent” results in RCT’s and did not conclude that e-cigarettes were effective as a therapeutic product for smoking cessation. (Patnode et al, 2021)

- The U.S. Surgeon General found that there was too much variation in the products sold and the way they were used to make generalizations about whether or not they were effective for smoking cessation. (U.S. Surgeon General, 2020).

Reviewers who considered both RCTs and longitudinal or observational studies have found no benefit to quitting with e-cigarettes. These include:

- A Swedish review of RCT’s and longitudinal studies that found no net benefit to the use of e-cigarettes for quitting smoking was found. (Hedman et al, 2021)

- A study following American smokers over time found no evidence that higher nicotine e-cigarettes (or lower nicotine cigarettes) improved successful quitting or prevented relapse (Chen et al, 2022)

- A US study looking at RCT’s and observational studies which found that although e-cigarettes were effective when used as therapeutic interventions in clinical settings, this was not the case when they were sold as consumer products in the general population. (Wang et al, 2021).

- Another study using the same longitudinal study found that dual users were less likely to quit. (Osibogun et al, 2022)

Relevant also is a study conducted by Environics for Health Canada, which followed vapers over a two-year period finding no net reduction in smoking (Environics POR 113-20)

Outside of the United Kingdom, very few medical bodies recommend e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. Those which advise doctors to refrain from recommending e-cigarettes to smokers include the College of Family Physicians of Canada and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. This summer, leading Canadian smoking cessation specialists Peter Selby and Laurie Zawertailo published a Clinical Practice review on Tobacco Addiction in the New England Journal of Medicine, concluding that even though they believed nicotine e-cigarettes may be more effective than nicotine-replacement therapy “We would recommend against the use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation given insufficient evidence to support their use.”

The role of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation is currently under review by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care.

This Cochrane review did not address the non-clinical (public health) consequences of e-cigarette use

There are a number of aspects of e-cigarette use that were not included in the Cochrane assessment, and many harms which were not included in their definition of “adverse consequences”. These include:

1) the increased health risks incurred by smokers who try e-cigarettes, but continue to smoke (dual users), thereby inhaling the different harmful chemicals in each type of product.

2) the increased health risks incurred by smokers who successfully quit with e-cigarettes, but who continue to use them. (The Hajek RCT found that those who successfully quit using NRT are half as likely to continue using nicotine as those who used e-cigarettes).

3) the initiation into nicotine use by young people who are influenced by messaging that encourages e-cigarette use.

4) the role of the tobacco industry in designing and supplying both cigarettes and e-cigarettes, and the commercial pressure that encourages them to market these in ways which maintain sales.

In the full (pay-walled) version of their report, the reviewers acknowledge this limitation of their study: “Reviews of ECs for policymaking are often broader in scope than our review, which focuses exclusively on their role in supporting smoking cessation in people who smoke. Outside of smoking cessation, there remain unanswered questions about the impact of EC availability and use on young people; we will be evaluating this in a separate review.”

There is no evidence that encouraging smokers to use e-cigarettes has benefitted health in Canada.

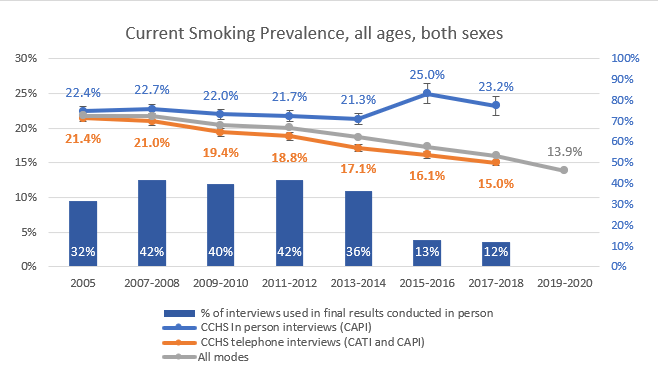

The federal policy decision in 2016 to liberalize the sale of vaping products as consumer goods remains controversial. Four years have passed since this policy became law with the 2018 Tobacco and Vaping Products Act)

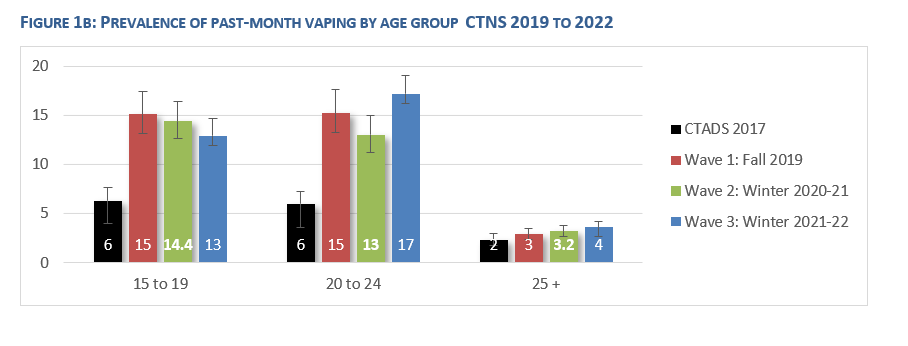

The impact of this policy change is reflected in federal surveys, which show that the uptake of these products was largely among young people, and not among adult smokers.

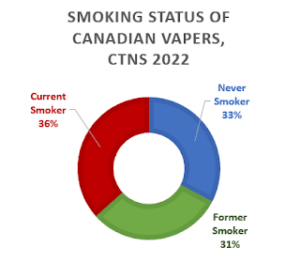

Although smoking rates continue to decline, Federal surveys show that this is chiefly due to the growing population of never smokers, and that the quitting rates in Canada have not increased since e-cigarettes were legalized.  Currently in Canada, two-thirds of e-cigarette users either continue to smoke cigarettes (36%) or have never smoked (33%).

Currently in Canada, two-thirds of e-cigarette users either continue to smoke cigarettes (36%) or have never smoked (33%).

More about the Cochrane reviews of tobacco interventions

Over the past 30 years, Cochrane (formerly the Cochrane Collaboration) has served health scientists by gathering, screening, reviewing and reporting on research on a wide range of health issues. The work of these scientists is guided by a conflict of interest policy which precludes reviewers from being employed in a commercial organization with an interest in the intervention, or having a direct commercial interest, such as owning a patent. Funding for the reviews can come from a variety of sources — this recent review on e-cigarettes was funded by Cancer Research UK.

Within Cochrane, the Tobacco Addiction Group (CTAG) is responsible for assessing tobacco-related science. This specialty group currently offers more than 80 reviews on tobacco-related topics ranging (alphabetically) from acupuncture to workplace interventions.

Some of these CTAG reports review the evidence on clinical topics (i.e. medicines, behavioural counselling, or alternative approaches like hypnosis and acupuncture). Others cover programmatic interventions (such as competitions, incentives, self-help materials and exercise programs). Public policy issues are also reviewed (like advertising, smoke-free spaces, or sales to minors laws.) Despite the preference for Randomized Control Trials (RCT), reviews sometimes include other study designs, like comparing population-level behaviours over time. In 2021, Cochrane updated its special collection on Stopping Tobacco Use.

(The Tobacco Addiction Group reports it is being disbanded effective March 2023 and says it is “no longer accepting any new submissions or proposals for reviews.”)

More about the Sixth Cochrane review of e-cigarettes

The estimate of the comparative benefits of e-cigarettes were based exclusively on clinical experiments that that made head-on-head comparisons of e-cigarettes and NRT by randomly assigning would-be quitters to trying e-cigarettes or using NRT. (Random Clinical Trials).

This group accepted only 6 RCT’s for their study — two of which had been written by members of the Cochrane review team. This is shown in the detailed results of their review (available only behind a paywall), which list the studies and the amount of weight each carried in arriving at the final estimate. Two fifths (41%) was based on a 2019 study by Peter Hajek and 16% on a 2013 study by Chris Bullen. (Drs. Peter Hajek and Chris Bullen and co-author Dr. Hayden McRobbie were among the 12-member Cochrane review team).

The Hajek study has been discussed here before, with attention to the ‘small-print’ findings that did not make their way to the core publication — namely that in this study NRT performed twice as well as E-cigs at achieving nicotine abstinence and preventing dual-use. Those assigned to use NRT group had more than double the success in ending nicotine use (7% vs. 3.2%). Those assigned to use e-cigarettes had a much higher risk of becoming dual users (25.1% vs. 15.2%). This Cochrane update similarly left the issues of dual use and nicotine abstinence unaddressed.

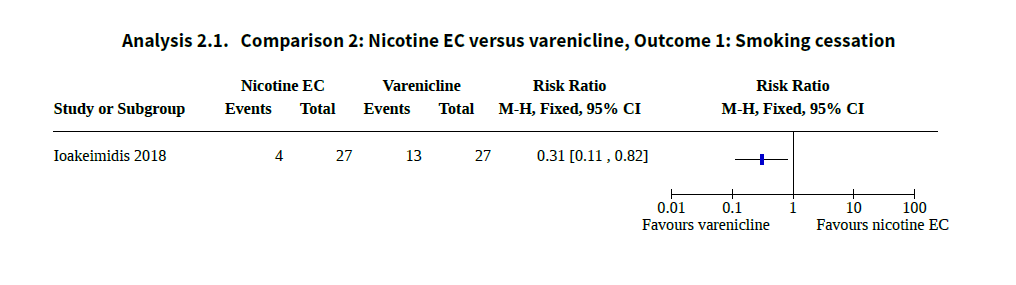

The ‘free’ version of the Cochrane review on e-cigarettes released last week mentions that a comparison was made with Varenicline (a stop smoking medication available on prescription), but fails to mention that in this comparison, e-cigarettes did poorly. The full report presents the results of one head-to-head comparison between varenicline and e-cigarettes. (Ioakeimidis, 2018). This small study found those who used e-cigarettes were one-third as likely to quit as those who used varenicline.