Over the last week, two major surveys on smoking and vaping commissioned by Health Canada were disclosed. Both were conducted by Environics Research and managed under the framework of Government of Canada Public Opinion Research. Reports on these surveys are available from the Library of Canada at the following links:

Both panels were designed to permit “return-to-sample” (RTS) reviews in which the same individuals are asked in future years about changes to their and/or vaping behaviours.

This is the second such RTS approach for vaping: the results of the panel in place between 2019 and 2021, reported here a year ago, found significant changes in vaping and smoking over the two year period. (Among the participants in this first panel, contrary to the results in the general public, smoking rates went up over the two years). The federal government currently has no longitudinal population surveys which include vaping or smoking behaviour.

Between them, these two new Environics studies cost over $450,000 and involved the recruitment of 4,815 vapers (Canadians over aged 15 who had vaped at least once a week over the past month) and 7,248 smokers (Canadians over aged 15 who had used cigarettes in the past month). The recruitment was conducted to allow for additional young people and communities of concern (indigenous, visible minority, LGBTQ2+) Over half a million Canadians were invited to take the survey and the participation rate was 14% (vaping) and 13% (smoking).

Both of the new survey reports (and the additional data on “banner tables”) contribute to our collective understanding of the perspectives of individuals who use these products and are therefore worthy of a careful read by the tobacco control community.

This post identifies some of the unique or surprising findings in these reviews.

1) Most smokers — and especially young smokers — do not find smoking unaffordable.

Smokers were asked “how affordable are the cigarettes you buy?” Only 1 in 5 Canadians said that cigarettes were unaffordable, and one-third reported they were affordable. As expected, smokers who lived in provinces where taxes are higher were more likely to report that cigarettes were unaffordable, as were smokers who had a smaller family income.

Large differences were seen in the perception of affordability by age. Only 1 in 10 teenage smokers and 1 in 5 young adults found cigarettes were unaffordable – compared with 2 in 5 adults .

2) One-third of young vapers and former smokers say that throughout the day they vape “continuously”

There are large differences in the frequency with which vapers report they use their devices. The highest frequency of use is reported by two mostly exclusive groups: teenagers and former smokers.

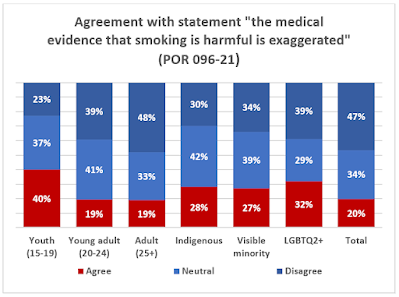

3) Many young smokers think that the dangers of tobacco are exaggerated.

Two in five teenage smokers agree with the statement “the medical evidence that smoking is harmful is exaggerated”. Among the general smoker population, one in five shares this view, but about half say that the dangers are not exaggerated.

Beliefs among Indigenous smokers are also different than the general population, with more than one-quarter (28%) saying that the dangers are exaggerated, and fewer than one-third (30%) say they are not. A similar pattern was found with other equity groups identified in this survey.

4) Smokers and vapers report similar patterns of first nicotine  dose of the day.

dose of the day.

For the most part, similar proportions of smokers and vapers say they use nicotine within 5 minutes of waking (the survey acknowledges that many smokers are vapers, but does not provide information on how soon after waking a cigarette OR a vaping product is used). Almost half of teenagers who smoke or vape do so within 30 minutes of waking.

Surprisingly, perhaps, no vapers identified “addiction” as one of the three main reasons they vape (QC2).

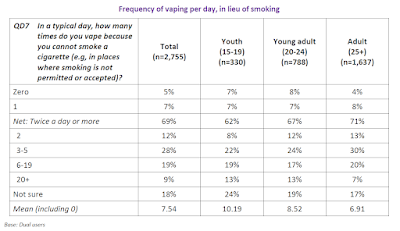

5) Dual users vape to overcome smoking restrictions on average more than 7 times a day.

5) Dual users vape to overcome smoking restrictions on average more than 7 times a day.

Over half of the vapers in this panel also use cigarettes (58%), with fewer than 1 in 5 being people who have transitioned from smoking to vaping (former smokers = 18%). One quarter (24%) have never been regular smokers, including the almost 1 in 5 (18%) who have never smoked a whole cigarette.

Dual users smoke an average of 8 cigarettes per day — almost all of which they identify as using to overcome barriers to smoking.

6) Vapers who have quit smoking are LESS LIKELY to say they have received advice from vape stores or health professionals.

Vapers who had previously smoked or who continue to smoke were asked with whom they had spoken about using vaping to quit or reduce cigarette use (results shown below). Those who had successfully quit smoking were more likely to report they had spoken with no one than were those who continued tdo smoke (37% vs 16%), and were less likely to report they had talked with vape store staff (20% vs 34%) or health care professionals (16% vs 29%). The most commonly reported discussions on vaping to quit were from friends and family.

A similar question was asked of those on the smoker panel who also vaped. Those results are shown on page 41 of Environic’s smoker panel report.

7) One quarter of those who currently smoke have formerly made a “successful” quit attempt.

Among the Smokers’ Panel, one-quarter (25%) had previously quit for more than six months: 18% of smokers had quit for more than one year before relapsing, and 7% had quit for six months to one year. Six months is the benchmark for a successful quit used in many studies on efficacy of stop-smoking approaches, and one-year is often used to define long-term quitter.

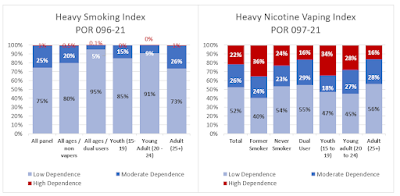

8) When dependency is assessed on the same basis for vaping and tobacco, “high dependency” is more often observed for vaping.

Environics used the “Heavy Smoking Index” parameters to assess how many Canadian smokers in their panel had moderate or high dependence on smoking. The index assigns a score based on how many cigaretets were smoked each day and how soon after waking the first cigarette was consumed. These researchers established a Heaviness of Vaping Index, which similarly identified high dependence for those who vaped with nicotine more than 21 times per day and within 5 minutes or waking, or 31 or more vapes a day and vaped within 30 minutes of waking.

Under their parameters, vapers were more likely to be defined as having high dependence.

Implications for public health

Health Canada continues to heavily fund and to rely on consumer research studies to inform its approach to tobacco and vaping. As reported here earlier, these reports are available to the public.

Nonetheless, this data on the Canadian experience with and use of nicotine products has not been translated into publications in peer-reviewed journals, and it remains on the ‘grey literature’ shelf. This hinders translating the Canadian experience into more generalizable conclusions, through systematic reviews or other knowledge development activities. A system to translate these reports into scientific publications could increase their value and use.

A limitation of the “panel” approach is that it is a closed system — looking only at the behaviour of the individuals initially selected. The first Environics vaping panel, for example, identified how many vapers moved from vaping to dual use or being nicotine-free, but was not structured to include those who moved from smoking to vaping. Half of the vapers included in the second vaping panel started vaping regularly over the past two years — at least one year after the first panel was struck.

Even with the new two-panel approach, the behaviour and beliefs of those who return to smoking or vaping (relapse) or who start smoking or vaping (initiation) will not be assessed. If the panel system proves effective, there may be some use in extending it to monitor beha