National Non-Smoking Week is 46 years old this month. This is an occasion to reflect on how much has – and has not – changed over the past half century. This post looks at parallels in government tobbacco policy in 1977 and 2023, and what lessons we might take from this history.

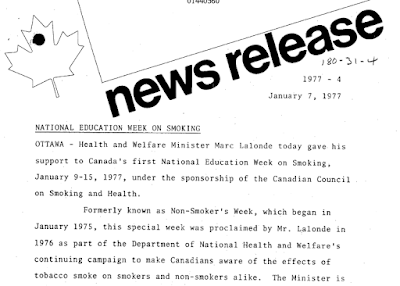

For many Canadians it was more than a lifetime ago that Health Minister Marc Lalonde designated a week in January 1977 as a time to focus on tobacco use. He said this was “part of the Department of National Health and Welfare’s continuing campaign to make Canadians aware of the effects of tobacco smoke on smokers and non-smokers alike.” The objective of the week was to encourage smokers to quit and “join the non-smoking majority”.

This year’s message from the health ministry has the same focus on individual behaviour change and the actions the government is taking to support smokers’ quitting and to protect youth from starting.

This year’s message from the health ministry has the same focus on individual behaviour change and the actions the government is taking to support smokers’ quitting and to protect youth from starting.

As did their predecessor, the Hons. Jean-Yves Duclos and Carolyn Bennett framed the week as an “opportunity to educate people across Canada about the benefits of a smoke-free life.” This year’s message was virtually identical to the one issued a year earlier, with the notable addition of a tacked-on sentence designed to encourage smokers to switch to vaping products.

Plus ça change ….

Much progress has been made to reduce smoking and the causes of smoking over these 5 decades. Cigarette smoking rates have fallen from 43% in 1977 to 12% in 2021. Smoke has largely been cleared from the spaces where Canadians work, play and live. Once-ubiquitous advertisements for cigarettes have disappeared from public view – even on cigarette packaging. In 1977, the government was against putting legislative controls on the market, but now they are firmly in place and are buttressed by provincial laws. Provincial government actions have put tobacco companies into bankruptcy protection.

Indeed, Canada has done better at reducing cigarette smoking than most other countries. A review of the reduction in (age-adjusted) smoking rates between 1990 and 2019 put Canada in 9th place.

… plus c’est la même chose

There are, however, some striking parallels between the government’s position on tobacco in 1977 and today. The first is a belief that new laws are not needed. The second is a belief that market forces can be leveraged to deliver harm reduction.

Although the term “harm reduction” is associated with this century, the idea of benefitting continuing drug users by reducing the risks of such behaviour is much older. Of the 5 main versions of Canada’s tobacco control program, three have included a harm reduction component.

1970s – 1980s: Less Hazardous smoking. Health Canada’s first efforts to reduce the harms of smoking involved encouraging smokers to leave longer butts and smoker fewer cigarettes. In the early 1970s the department seized on the idea of pressuing manufacturers to reduce the amount of tar in cigarettes. The “Less Hazardous Cigarette” program also involved supporting the development of new types of tobacco to decrease the amount of tar in comparison with nicotine. The department’s interest in reducing tar was high: the 1977 tobacco policy included “reducing the hazard to smokers” as one of its 4 main goals. (The others were protection from second hand smoke, prevention of smoking initiation and support for cessation).

1970s – 1980s: Less Hazardous smoking. Health Canada’s first efforts to reduce the harms of smoking involved encouraging smokers to leave longer butts and smoker fewer cigarettes. In the early 1970s the department seized on the idea of pressuing manufacturers to reduce the amount of tar in cigarettes. The “Less Hazardous Cigarette” program also involved supporting the development of new types of tobacco to decrease the amount of tar in comparison with nicotine. The department’s interest in reducing tar was high: the 1977 tobacco policy included “reducing the hazard to smokers” as one of its 4 main goals. (The others were protection from second hand smoke, prevention of smoking initiation and support for cessation).

The federal government’s actions to reduce the tar in cigarettes was examined in great detail during the Blais and Létourneau trials. Tobacco companies were successful in their attempts to use government policy as a defence for damage caused by misleading advertising of light cigarettes.

Health Canada’s enthusiasm for “less hazardous smoking” did not last much longer than a decade. After a change in government, legislation became an option and a new strategy was developed to reflect this. The 1988 National Strategy to Reduce Tobacco Use (NSTRTU) was a consensus framework adopted also by provincial governments and civil society organizations, and did not include a harm reduction component. However, it was not until 2001 that the department formally abandoned support for ‘light’ cigarettes. (It also took decades for scientists to agree that the popular belief that light cigarettes were less harmful was not substantiated).

2001-2006: Product Modification. The NSTRTU effectively died in 2001, when the federal government stepped away from a pan-Canadian approach and adopted its own Federal Tobacco Control Strategy. Once again, the goal of reducing harm to continuing smokers was formally included in the department’s four key objectives. The approach it proposed was product modification – and it committed to “explore ways to mandate changes to tobacco products to reduce hazards to health.” When the strategy was tweaked in 2007, this component was dropped.

2018: Vaping as reduced harm. In 2018, Health Canada adopted Canada’s Tobacco Strategy, This revision also included harm reduction, but this time it was characterized as switching to vaping products.

Over the past 4 years, the public-facing elements of Canada’s Tobacco Strategy have been quietly reworded: among other changes the term “harm reduction” has been replaced with “reduce the harms”, but the general approach does not appear to have changed. In the departmental review of the file, released last month, the department identified that while no changes to the law are needed (“amendments at the level of the Act are not necessary at this time”), it did see the need to encourage smokers to see vaping as less harmful than smoking. (“Work could be undertaken to communicate the relative risk of smoking, in comparison to vaping, to people who smoke.”). This departmental sentiment strongly echoes its 1970s approach.

The parallels between “less hazardous smoking” and “reduced harm from vaping”.

Health Canada’s approach to reducing harms in 2022 parallels its view in 1977. In both decades the department has based its policy on a set of beliefs:

- That products which emit fewer chemicals will cause less disease.

- That smokers will be willing to switch products to satisfy their nicotine addiction.

- That market forces can be leveraged to encourage smokers to switch

- That shifting smokers to newer types of products does not require additional regulatory constraints on pre-existing products

- That efforts to encourage the use of “less harmful” products will not cause collateral damage by drawing in more new nicotine users than would otherwise be the case.

The post-legaliation reality

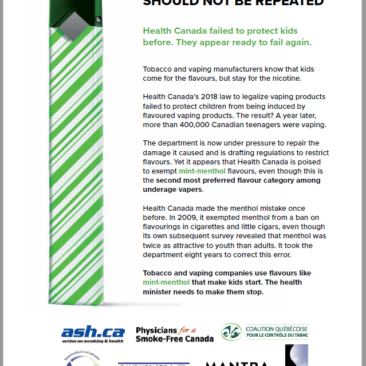

Health Canada has faced a harsh reality check since allowing vaping products to be sold as consumer products in May 2018. It continues to struggle to “balance” the objectives of reduced harm to continuing nicotine users and protecting young people from nicotine use – but it has failed to satisfy either goal.

In the four years since the government legalized the vaping market there has been no evidence of a reduction in the overall harms to Canadian smokers that can be attributed to vaping. Smoking rates have fallen — but only because of an increase in never smokers. Vaping has not increased the number of former smokers (switchers). In the only studies which took a longitudinal approach for which results have been released, there has been no evidence that vapers were more likely to quit than smokers. Among the group of vapers followed for two years there was no overall decrease in smoking.

On the other hand, there has been abundant evidence that the government misjudged the impact of its policy on young people. Decades’ long progress against nicotine initiation has begun to reverse.

On the other hand, there has been abundant evidence that the government misjudged the impact of its policy on young people. Decades’ long progress against nicotine initiation has begun to reverse.

The department responded to the dramatic increase in youth vaping by introducing several controls on the market – most of which were called for by health groups before the legislation was adopted. It has not yet, however, agreed to change the law to apply equivalent framework to vaping as exists for tobacco.

These new measures have been slow to come on line. It has taken years rather than months to curb promotions and cap nicotine concentration. In June 2021, the government indicated that flavourings other than tobacco and mint-menthol would be banned in vaping products. 19 months later these regulations have not been finalized, no projected timeline has been provided and this restriction was not included in the regulatory commitments included in this week’s message from the ministers. Other important controls on packaging and product design or better barriers to youth access and price promotions are not even on the federal agenda.

Can we hope that other parts of history will repeat?

To the benefit of Canadians, in the 1980s Health Canada eventually abandoned its hopes that lower tar cigarettes would save lives and that it could motivate companies to market their products in ways which reduced harm. Instead, in the mid 1980s, it worked towards increased regulatory controls on the market, collaboration with other levels of government, and the engagement of civil society.

It did this by involving health stakeholders in the design of the National Strategy to Reduce Tobacco Use. The “Consultation, Planning and Implementation” committee was given the mission that foreshadows our modern goal of a Tobacco Endgame: “a generation of non-smokers by the year 2000.”

The NSTRTU ditched “less hazardous” but launched many new lines of action: “Legislation, Access to Information, Availability of Services, Message Promotion, Support for Citizen Action, Intersectoral Policy Coordination, Research/Knowledge Development.” Responsibility for these was to be shared with “comprehensive action by all groups concerned, using the various means available to them.”

In its desire to leverage commercial activity to achieve tobacco harm reduction, Health Canada again finds itself without much support or engagement of other levels of government or civil society partners. As it did in the 1980s, it can overcome this isolation by supporting the development of a new national strategy.

Canada needs an approach to tobacco and nicotine which seeks to end nicotine addiction in a multi-product market, and which leverages the unique opportunities presented by a bankrupt tobacco industry.