The overarching objectives of these recommendations are to protect young people from inducements to use vaping devices by regulating such devices as equivalent to tobacco products, and to encourage smokers who use vaping devices to use them solely to end or reduce their use of all nicotine-containing products.

Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health

January 2020

In early 2020, a few weeks before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, Canada’s Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health (CCMOH) issued their third statement about vaping. The occasion was National Non-Smoking Week, and the focus was on the need to intensify regulations on vaping products and to re-construct the policy approach to this market.

This post tracks the development of regulations which respond to those recommendations. Over the past 24 months, eight provinces, three territories and the federal government have amended their legislation or regulations in order to strengthen controls on the vaping product market.

No apparent progress, however, has been observed towards the CCMOH recommendations that a new and broadened regulatory approach towards nicotine products be established, or that nicotine product manufacturers be required to provide evidence that their products will benefit the public before they can be marketed.

Links to additional information, including a downloadable summary of this progress, are provided at the bottom of this post.

MARKET REGULATIONS

Flavour bans

The CCMOH called for a ban on all flavoured vaping products (with exemptions for some flavours), either by federal or provincial governments.

At the time of the recommendation only one province (Nova Scotia) had decided to ban all flavours but tobacco, which was put into force on April 1, 2020. Two other provinces followed suit: Prince Edward Island (March 1, 2021) and New Brunswick (September 2021). Nunavut passed legislation to ban flavours in 2021, but this has not yet been proclaimed into law. The Northwest Territories recently initiated a consultation process on the topic. Three provinces now only allow the sale of most flavours in specialty vape shops (Ontario, July 2020; British Columbia, September 2020; Saskatchewan, September 2021).

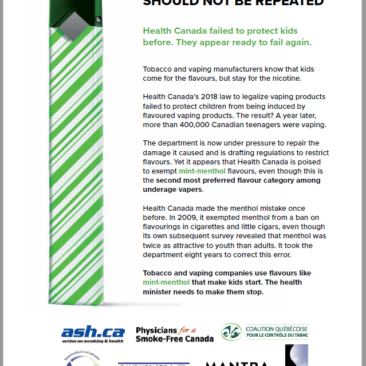

Last June, Health Canada published draft regulations that would ban flavours other than tobacco, mint, menthol, as well as prohibiting sugars and sweeteners and restricting the flavouring ingredients that could be used.

(In the past two years six European countries have introduced legislation to ban flavours: Denmark, Hungary, Netherlands, Ukraine and Lithuania. Such measures were adopted in Finland in 2016 and Estonia in 2019.)

Nicotine restrictions

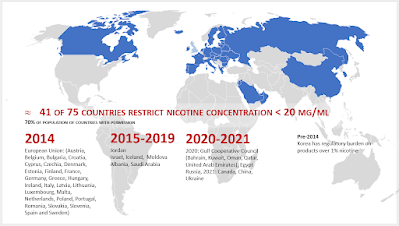

The CCMOH called for the nicotine content in vaping products to be limited to a maximum of 20 mg/ml. It also called for the development of other standards on nicotine delivery, such as temperature or the use of nicotine salts, if evidence supported these measures.

As a result of Health Canada regulations, nicotine concentration of vaping liquids was capped at 20 mg/ml effective July 23, 2021. Two provinces had earlier imposed this standard: British Columbia and Nova Scotia, both in September 2020.

(The 20 mg/ml maximum has been adopted by 41 countries, covering 70% of the population living in countries where e-cigarettes are permitted for sale.)

Safety requirements for ingredients

The CCMOH called for constituents of e-liquids to be regulated on the basis of their potential to cause harm when inhaled rather than oral ingestion.

The federal government is the only Canadian jurisdiction which is proposing to restrict the ingredients that can be used in vaping products, and some ingredients are already banned. These restrictions are based on the impact of the ingredients on flavour sensation or colourings, not on inhalation risk. (In the proposed revised Schedule 2 to the federal law, Health Canada is proposing to permit the use of some flavouring agents which are known to be harmful when swallowed or inhaled, including estragol, furfurl alcohol, pyridine, isophorone and others.)

Taxation

The CCMOH called for vaping products to be taxed “in a manner consistent with maximizing youth protection while providing some degree of preferential pricing as compared to tobacco products.”

Four provinces have imposed specific excise taxes or higher sales taxes on vaping products than on other consumer goods. B.C. increased the PST on vaping products from 7% to 20% (January 2020), Nova Scotia has a tax of $0.50 per millilitre of liquids (September 2020), Newfoundland and Labrador has a 20% tax on devices and liquids (January 2021) and Saskatchewan increased its sales tax on those products from 6% to 20%.(September 2021).

The federal budget delivered in April 2021 proposed a specific excise tax of $1 per 10 ml of vaping liquids or fraction therefor (effectively a minimum tax of $1 per pod or other unit sold). A consultation on the tax was held, and the government indicated that the tax will come into effect “in 2022”.

Age 21

The CCMOH called for the minimum age to be sold tobacco or vaping products to be increased to 21 years.

Both federal and provincial governments have minimum age laws. The federal minimum age remains 18, and only Prince Edward Island has raised the minimum age to 21 (March 1, 2020).

(In late 2019, the United States raised the minimum age to be sold tobacco or vaping products to 21, joining at least 7 other countries which ban the sale of tobacco to younger people – Sri Lanka, Mongolia, Honduras, Uganda, Ethiopia, Philippines, and Singapore).

Age-gating

The CCMOH called for requirements for age-verification of internet purchases of vaping products that are the same as those required for cannabis.

In April 2021, Health Canada included the development of “Amendments to the Tobacco Access Regulations (Age Verification for Online Sales)” in its Forward Regulatory Plan. The department indicated that the proposed regulation would identify the “mechanisms that must be undertaken to verify age and identity in the context of online sales.” No further information has been made public.

Promotion

The CCMOH called for the federal government to restrict the advertising/marketing/promotion/ sponsorship of vaping devices in a manner consistent with maximizing youth protection and to allow adult-oriented marketing if aimed solely at supporting adult smokers ending or reducing their use of all nicotine-containing products. It called on provincial governments to ban all point- of-sale advertising other than in adult-only specialty vape shops.

Since 2020, federal regulations on vaping product promotions have been put in place. These regulations forbid advertisements that can be seen by youth (” a vaping product or a vaping product-related brand element must not be promoted by means of advertising done in a manner that allows the advertising to be seen or heard by young persons.”).

All provincial governments have passed legislation to ban point-of-sale advertising where it can be seen by children. The federal regulation also prohibits these ads.

Federal regulations permit some forms of advertising to adults, but neither they nor provincial regulations restrict ads based on whether they are linked to supporting ending or reducing nicotine use.

Packaging

The CCMOH called for the federal governments to require plain and standardized packaging along with health risk warnings for all vaping products

Federal government requirements for health warnings on vaping products came into force on July 1, 2020. The only health risk identified in these warnings is addiction.

The federal government does not currently propose to require plain packaging of vaping products, but one province has taken steps in this direction. British Columbia‘s E-Substances Regulation allows the sale of vaping products only when “packaged in a plain manner that does not contain any text or image other than as required or permitted under this section.”

Pre-market requirements.

The CCMOH called for the federal government to require product manufacturers to disclose all ingredients of vaping devices to Health Canada as a condition of being marketed, including establishing consistency in reporting nicotine levels in both open and closed vaping systems.

Health Canada has indicated its intention to require vaping manufacturers to report such information. In the Forward Regulatory Plan 2021-2023, it identifies that “Vaping Product Reporting Regulations” will be developed, and that draft regulations would made public this winter.

Retail Licensing

The CCMOH called for provincial governments to require a vendor’s licence for those selling vaping products.

Five provinces have adopted requirements for retail licenses or have imposed registration requirements on retailers who wish to sell vaping products: Quebec (2015), British Columbia (July 2020), Nova Scotia (July 2020), Newfoundland and Labrador (2021), New Brunswick (April 2022). In Prince Edward Island, vaping products may only be sold in specialty stores that meet specific requirements, although a license is not required. Ontario requires specialty vape stores to be registered with local health authorities.

ADMINISTRATION AND GOVERNANCE

Enforcement

The CCMOH called for the federal government to enhance compliance, enforcement and public reporting and called on provincial governments to routinely use youth test purchaser.

Health Canada has subsequently made public the result of its enforcement activities, and has reported on the results of three rounds of inspections of vaping retailers. In December 2021, Health Canada disclosed that it “has not pursued any prosecutions against regulated parties manufacturing or selling vaping products under the TVPA.”

As reported earlier this month, there is limited information on the results of compliance activities underway in Canadian provinces.

Health Education

The CCMOH called for governments to collaborate to enhance public awareness and educational initiatives on the risks of vaping products, targeted at young, parents, educators and health care professionals.

There is no consolidated report on such activities. Health Canada runs a “Consider the Consequences” campaign directed at young persons, with a 3-year budget of $12 million. Reported expenditures for Health Canada’s Youth Vaping Prevention Campaign were over $6 million in 2019-2020.

Cessation support

The CCMOH called for governments to establish comprehensive cessation initiatives for people with nicotine addiction, especially for youth.

There is currently no consolidated report on such activities. Health Canada has provided financial support for the development of programs to support vaping cessation among younger Canadians, as have some provincial governments.

Health Research

The CCMOH called for governments to monitor and research and short and long-term health effects of vaping products and to research the effectiveness of policy approaches to address youth vaping.

In 2020, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research with the Canadian Cancer Society awarded 27 grants for research directed to the health effects of vaping and policy approaches to address youth vaping. Through its Substance Use and Addictions Program, Health Canada has provided support for the development of youth vaping cessation interventions and research on policy development.

The CCMOH called for governments to research the effectiveness of vaping products in supporting smokers to end or reduce their use of all nicotine-containing products.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care has conducted a systematic review of evidence on ‘Tobacco Smoking in Adults’ and is currently preparing draft guidelines. These are expected to be released in 2022/23. It is not clear that this will address “ending or reducing their use of all nicotine-containing products”, which is not an identified goal of the federal Canada’s Tobacco Strategy.

Monitoring and Surveillance

The CCMOH called for federal and provincial governments to enhance surveillance and reporting of vaping product use and population health impacts.

Since January 2020 national surveys have been established or expanded to include vaping use. These include Statistics Canada’s annual Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, which was conducted in the winter of 2019-2020, 2020-2021 and is currently in the field for 2021-2022. The results of the first two waves have been made public. Since 2020, Statistics Canada’s annual Canadian Community Health Survey has included questions on e-cigarette use, although this data not yet been released.

Health Canada has supported consumer research on vaping product use, including a vaper panel which has monitored behaviours of some individuals over a two-year period.

Other national surveys were diminished in this period. The formerly bi-annual Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drug Survey was last conducted in 2018-2019. It did not take place in the 2020-2021 school year, as an apparent result of a delay in changing suppliers. The contract was awarded in December 2020 to CCI Research and the survey is in the field for the 2021-2022 school year. Federal funding supports the COMPASS survey, which is conducted in selected schools by University of Waterloo.

Provincial surveys on vaping behaviours in the general population are conducted in some provinces, (including Quebec and Ontario) as are provincial surveys of young person’s vaping (Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia).

Policy Revision

The CCMOH called for governments to work together to develop a broad regulatory approach to all alternative methods of nicotine delivery (i.e. other than tobacco products). They recommended that a component of any such regulatory approach should be the requirement for manufacturers to demonstrate that marketing new products is in the public interest.

No efforts to develop such a regulatory approach have been made public.

(Premarket authorization is the approach now required by the U.S. Food and Drug Authority for e-cigarettes and novel tobacco products).

Resources-Fact sheets: