In Canada, tobacco control is an area of shared jurisdiction: both federal and provincial governments have wide authority to regulate the manufacture, promotion, distribution and sale of tobacco products. Although Canada’s constitution generally gives provinces control over commercial activities, the Supreme Court long ago recognized the authority of the federal government to also regulate cigarette promotions and products.

Despite differences in emphasis and intensity, the tobacco control regulations and programs in each province are largely similar. A province that might be “leading the pack” in one aspect (eg flavour restrictions) may not be so far ahead with others (eg taxes). Added to these differences are significant demographic and cultural differences across Canada’s wide geography.

This post looks at data on smoking behaviour in Canada’s provinces, based on 9 cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) spanning almost 2 decades. The information presented below is for the general population. Data disaggregated for sex and age are available on the following interactive tables:

- Provincial Smoking Behaviour 2000 to 2019: CCHS (6 indicators)

- Provincial Smoking Behaviour 2000 to 2017-2018: CCHS (4 indicators) – age and sex

- Quitting history 2000 to 2017-2018

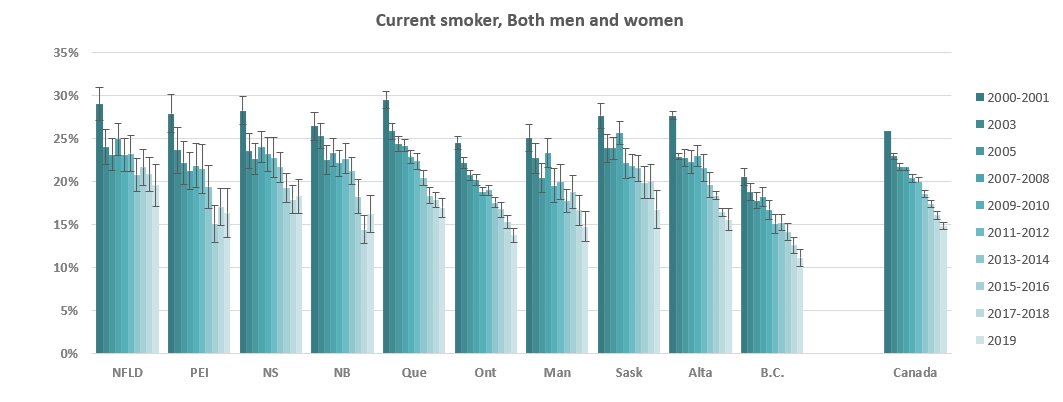

Smoking rates have fallen across the country

Smoking rates across the country have fallen by almost one-half (a 40% reduction) between the first cycle of CCHS (in 2000) and the period for which complete indicators have been released (2017-2018).

Over the past 2 decades, for each group of 200 Canadians, every year there has been one less person who smokes every day or on occasion. This pattern holds true in most provinces.

The standings between the provinces have not changed greatly in 20 years. Those with the lowest smoking rates in 2017-2018 are essentially the same as those with the lowest rates 18 years earlier – British Columbia and Ontario. Although smoking rates have dropped by a greater proportion in some other provinces, they have not yet caught up.

The reduction has been greatest with respect to daily smoking. Since 2000, the percentage of Canadians who smoke daily has fallen by more than 11 percentage points (11 people in 100). The provinces with the largest declines in daily smoking are Quebec and Prince Edward Island (13.5 percentage points).

There has been very little change in occasional smoking. There are more occasional smokers in 2017-2018 than in 2000 (1.5 million to 1.1 million). The increase in the rate of occasional smoking is slight but statistically significant (from 4.5% to 4.8%). During this period, the overall population grew by over 5 million people. The profile of occasional smokers (and the number who were once daily smokers) will be explored in a future post.

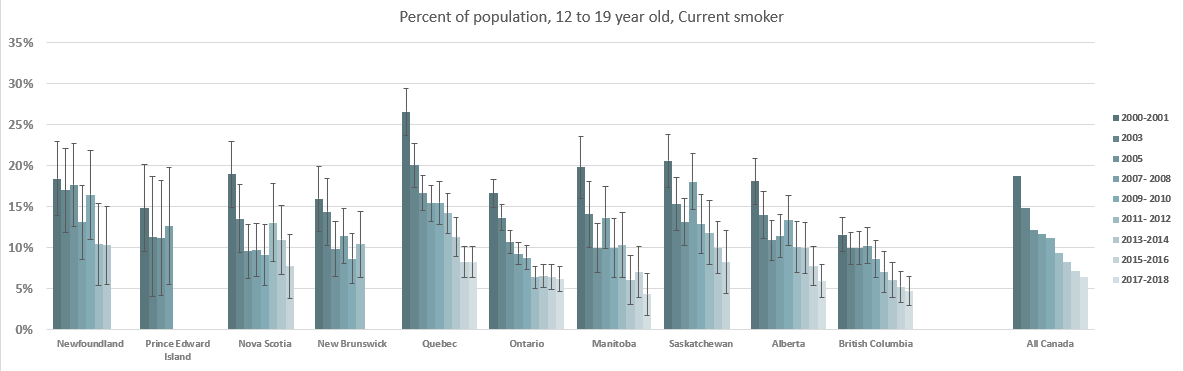

The greatest drop in smoking has been among the youngest Canadians

Current smoking among teenagers has fallen by two-thirds since 2000. Those born in the 1980s were 3 times more likely to smoke as teenagers than those born in the first decade of this century (19% vs 6%). Comparisons among all provinces have become more difficult, as surveyors are unable to find enough young smokers to provide a reliable estimate for the smaller jurisdictions. Among the larger provinces, Quebec rates for teen smoking (age 12 to 19) have fallen from 27% to 8%, compared with Ontario’s drop from 17% to 6%, Alberta’s from 18% to 6% and British Coumbia’s from 12% to 5%.

Fewer and fewer Canadians ever try smoking…

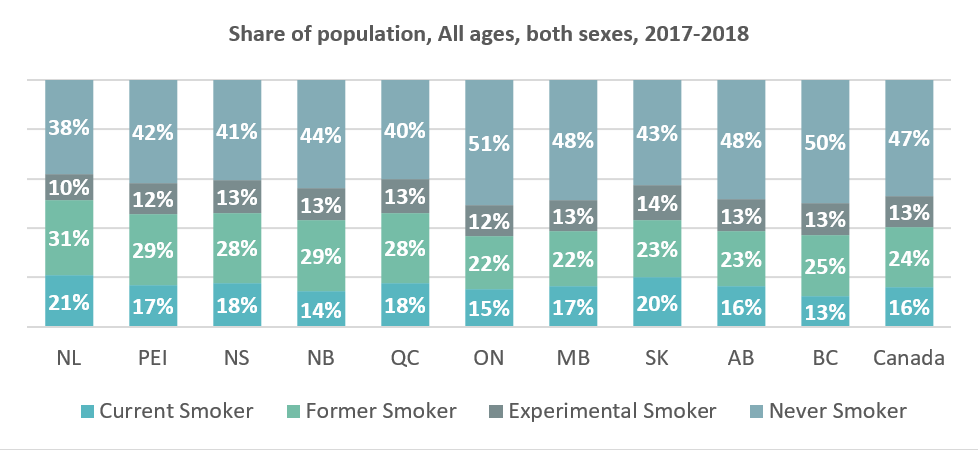

As we observed earlier for Canada as a whole, it is the growth in the “never smoking” population that is likely driving reductions in smoking.

This is especially true in some provinces. For example, British Columbia and Ontario are also the provinces where people are most likely to have never smoked a single cigarette. In Ontario and B.C., one-half of all citizens and 6 in 10 people in their 20’s have never smoked a single cigarette (compared with 5 in 10 in the other provinces).

Ontario and Quebec provide an example of this. Although Ontario has a lower smoking rate than Quebec (15% vs 18%), the percentage of Quebec smokers who have quit is no lower. The Quit Ratio of former to current smokers is 1.42 in Ontario and .1.59 in Quebec. Ontario’s relative success can more likely be attributed to fewer people having begun smoking. One-half (51%) of Ontarians have never smoked one cigarette, compared 40% of Quebeckers.

… and more smokers have quit.

Overall, the proportion of Canadians who have smoked and then quit has grown slowly, although progress has been uneven across the Country.

British Columbia is also in the lead for this indicator: in that province there are 4 former smokers for every 2 smokers, compared with a national average of 3 former smokers for every 2 smokers.

All provinces are doing much better than they were in 2000 – with relatively greater improvements in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick.

The prairie provinces are doing least well at moving smokers to former smokers. One contributing factor is the relative youthfulness of prairie populations, and the greater likelihood that older smokers will have quit: the median age in the prairies (36) is a full 5 years younger than in B.C. (41).

(Although fewer smokers are quitting every year)

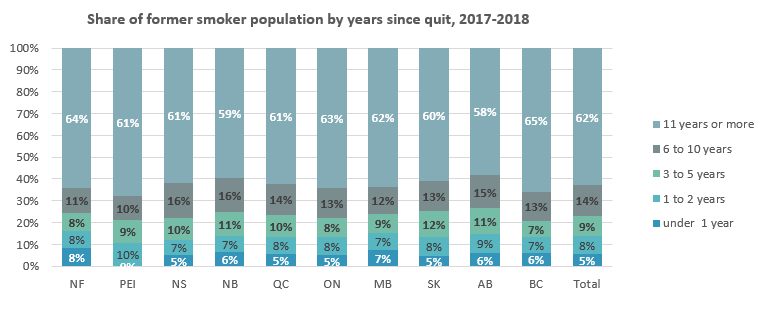

Since 2003, this survey has asked former smokers how long ago they quit. From this we know that the number of Canadian smokers who have quit in the past year has fallen from almost 700,000 in 2003 to 414,000 in 2017-2018.

To some extent this should be expected, given that with a falling smoking rate there are fewer remaining smokers year on year. Nonetheless, even as a proportion of remaining smokers, the number of “recent quitters” is not growing. It would appear that in most provinces, smokers are no more likely to quit in 2017-2018 than they were 20 years ago.

As a result, most former smokers are long-term quitters. Two-thirds of former smokers in Canada quit more than a decade ago, with very few differences across the country.

In fact, death is more responsible for reducing the number of Canadian smokers than quitting. The CCHS shows that for every 10 fewer Canadian smokers in 2018 than there were a decade earlier, there were only 4 more former smokers. The other 6 smokers had disappeared from the CCHS population, mostly likely through death. (During that period, there were 1 million fewer smokers, but only 429,000 more former smokers).

- Individual and community efforts to reduce smoking have succeeded in Canada at a steady if slow pace for the past 20 years.

- British Columbia has maintained its lead for two decades. Other provinces are generally keeping pace with B.C., and some have made relatively greater progress on some indicators (eg. youth smoking).

- Falling smoking rates reflect reduced number of people who start to smoke and increased number of smokers who successfully quit.

- Some provinces are doing relatively better than others at protecting youth from smoking and from achieving successful population cessation.

- Demographic differences between the provinces may be responsible for some differences between provincial smoking, starting and quitting rates.